“It was a home grown kind of insurgency:” Nancy Peckenham on Guatemala

July 18, 2014

I first became acquainted with Nancy Peckenham, an American activist, documentarian, and journalist, through her donation to Interference Archive, an extraordinary collection of posters from the 1970s and 1980s, expressing solidarity with people’s movements in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. A few months ago, I reached out to Nancy and was able to interview her over Skype about her history as an activist, organizer, and member of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala. Selections from Nancy’s donation can be seen in Interference Archive’s current exhibition, We Are Who We Archive, on view through August 3.

–Louise Barry

LB: Why did you collect and save these materials? What made you want to give them to Interference Archive?

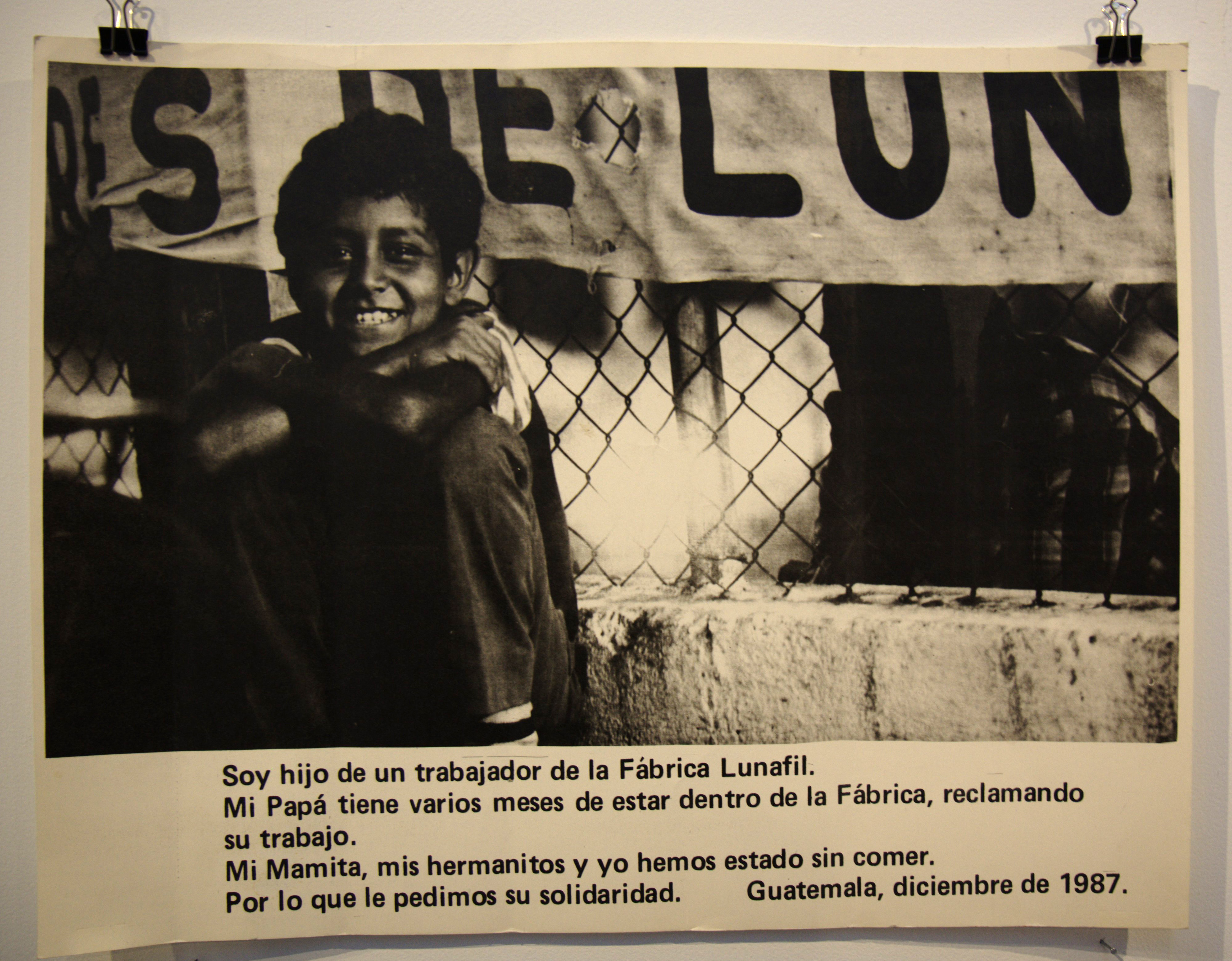

NP: I collected them because I thought they were really beautiful, and I thought they were really important as a way of communicating to the public about what was going on in Guatemala and Central America.

I’ve saved them for thirty-plus years. I’ve moved them, and I can tell you how many times I’ve moved them—four, five, six, seven, about eight times. [laughter] I enjoy looking at them. I thought that other people would hopefully see some value in them, and that I’d rather have them be taken care somewhere where there existed the possibility that someone else might get something out of seeing them, instead of hog them to myself.

LB: Tell us about your history with Guatemala.

NP: I got involved after I went to Guatemala in 1979 and I did research on land reform. I knew that armed groups were active in the countryside, but more important to me was the number of people being murdered by paramilitary forces, from intellectuals in the city to campesinos, primarily indigenous, in the countryside, where the army was very threatened by the support for the guerillas. So they began attacking entire communities. So I went down there, I did the study about land reform, and I had an advisor at the State Indigenous Institute who was a lawyer, who also would go back to his village, and advise people about how to get a title to their land. Which was a big deal back then down there. My advisor ended up getting assassinated, and I just felt like the world needed to know what was going on in Guatemala, so I did two things. I began a freelance journalism career, and I started writing about human rights violations in Guatemala for a church publication. And I started making documentaries.

The thing that was different about Guatemala from El Salvador, just to kind of go back in history a little bit, there was the Sandinista War in Nicaragua, which ended in 1979 when the Sandinistas took over Managua, and that was a very high-profile movement. Bianca Jagger, who was married to Mick Jagger, was Nicaraguan, and so a lot of celebrity types were publicly speaking out. And then in El Salvador, where the war moved next, again a lot of people got involved, a lot of celebrities, and there was a feeling that in Guatemala, it was much more of a home grown kind of insurgency. I got involved in Guatemala originally because I was doing anthropological research there. And I was very concerned about the indigenous people and the attacks on the indigenous people. Some of the posters from Guatemala–I’m looking at the 1982 calendar, that has the four or five revolutionary groups up, and a quote from an old Mayan text–there was something a little more home grown about the graphics that they did. And that always appealed to me.

And then, in 1982—I’m not sure of the sequence of this—but two things happened. One, I made a documentary film in the refugee camps in Mexico, and I published a book about Guatemala, that’s an anthology with three other editors, about the history of armed struggle, against the Spanish, and then, against the current government.

LB: And what was the book?

NP: It was called Guatemala in Rebellion:Unfinished History. After that, I went on to do another book called [singing] dun dun dun! Honduras. And this book, it’s called Honduras:Portrait of a Captive Nation, unbelievably, this book is about the only book ever written about the poor and overlooked country of Honduras. And I just saw it on Amazon for $2500. That’s more money than I was paid to put the book together!

LB: Can you talk a little more about your work making documentaries in Guatemala?

NP: The first documentary was called Camino Triste, and that was in the Guatemalan refugee camps. And then, I started working with a filmmaker named Ilan Ziv—Tamouz Media is his company–and with Marty Lucas. And we made another documentary—that one started in the refugee camps, but then we went inside Guatemala and we were using our search as a vehicle to see the impact of the counter-insurgency in the highlands. The name of that film was Journey to the End of Memories. Then, Ilan and I and a sound guy, Eddie Becker, did make another human-rights-oriented film in Peru and that was called Fire in the Andes. I didn’t have any formal training in filmmaking, but fortunately Ilan and my other colleagues did. I just had a lot of knowledge about Guatemala, and that’s how I got into being a producer.

LB: What kind of response did the documentaries receive when you showed them in the United States?

NP: The first one, Camino Triste, was shown on PBS, and people did give some feedback to PBS and to the series that ran it. You know, we showed it primarily as a fundraising tool. Because we were trying to get wealthy New Yorkers to donate money to the refugees and to our work, and it was really an educational piece. That was Camino Triste. Then the other film, Journey to the End of Memories, was a little bit more of a storytelling film, and a lot more kind of policy-oriented people responded to that one, because there’s one sequence in it where we visited what basically is a re-education camp where the army had rounded up all of these scattered villagers and brought them into a “new beginning” camp, and they had to get up every morning and line up, and there were hundreds of people there, and they’d have to sing chants, repeat chants supporting the government. And it was really like a re-education camp. You know, “como se yama le patria?” “What is the name of our country?” “Guatemala!” and everyone would go and raise their arms. It was really scary, because of course, no-one would talk to us because they were afraid of repercussions of any kind, but it was evidence of a re-education camp that would have impacted US aid to Guatemala. That was always another goal of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala and CSPES, to cut off US aid to these countries.

LB: Was it challenging trying to get people to focus on Guatemala or trying to raise money? Did you find that it was hard to get your message across?

NP: Well, it was harder than it was to get El Salvador’s message across because El Salvador was in the front page almost every day. So it was much more focused on people who were concerned about cultural survival, indigenous rights and human rights. Whereas we just didn’t have as broad of an audience so it was harder, and ultimately, we never really raised the kind of money that I would have liked to have seen and I think other members would have, but, we also were doing it because we wanted to–we really wanted to be part of the struggle. We wanted to be doing our small part. We worked a lot with Rigoberta Menchu when she came to the United Nations. And she would come with a delegation of two or three other people and they used to stay in different people’s apartments. She stayed in my apartment many, many days and they were part of a delegation that was trying to get the language in the UN charter changed to include their struggle, which is very kind of monotonous, bureaucratic work, in my humble opinion—but everyone was doing their little bit because on a certain level, changing the language at the UN was very important. And they came back for like three winters and stayed in New York for a month and went to the UN every day to try and do this. We were just part of that.

There was a place called El Taller Latino Americano, on West 19th st, which was a loft up on the 2nd or 3rd floor, and everybody would get together and we’d have a show of these educational films, and speakers who had been out in the field, if they were recently exiled they would come and go on a speaking tour and they’d speak and then we also had dance parties all the time. We felt we were educating ourselves and we also felt we were taking our message and education to the community.

LB: How did you get involved with the Committee of Solidarity with the People of Guatemala? What were some of your roles within the group?

NP: When I came back to New York in 1980, I wanted to do more, so I found this group of primarily Guatemalans in Brooklyn. They lived off of Myrtle Avenue somewhere, most of them. They were fighting to get attention in the media, and to build a movement, and so I became one of a group of about six of us and we formed coalitions with CISPES, which is the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador, which was much bigger and well-known. We would be invited to speaking engagements around the city, I remember because it was the first time I’d ever spoken publicly and I was scared to death, but we did it, and then, working with CISPES, that’s when we started having these coalition meetings. We would all work together. I guess you could say I was on the outreach committee of the coalition of CISPES, and the anti-intervention in Nicaragua, and then the Committee in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala, which is really the place where I did the most work.

LB: And were you one of the few people who was involved who was not Guatemalan? Or were there a lot of Americans?

NP: Actually, interestingly, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala was majority Guatemalan. Unlike CISPES, which was majority American. All of our meetings were conducted in Spanish which is actually how I learned to be good in Spanish, being at the meetings and really totally being forced to speak in Spanish all the time because we would get into these heated discussions. That’s why I say it was a little more home grown.

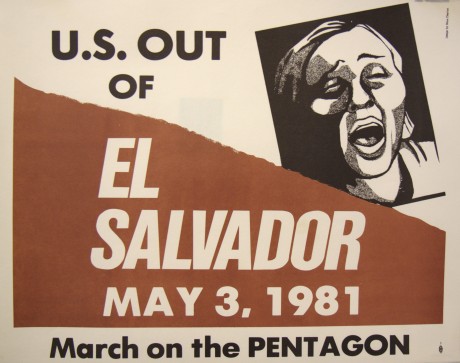

LB: One of the posters you donated to Interference Archive was from the march on the Pentagon on May 3, 1981. Were you part of that march?

NP: I was there. That was the first big march on DC. I don’t remember too much, other than walking down the street and chanting slogans and making sure that the speakers appeared in approximately the correct order.

I loved all the demonstrations. We had a great time. And we felt like we were making a difference. Although it was always very disappointing to see the mainstream media play down what we felt was very significant. But I always felt like posters and t-shirts were a way of communicating your message. When I worked for a labor union, I did communications work and I used to tell people, put your message on a t-shirt. It’s free.

LB: For people coming into the archive, who are going to be seeing some of these posters, what do you think is important for them to know, in order to understand the context in which they were created?

NP: People should know how important the struggle was to a whole section of people in New York City, where I was based. There was a great feeling of momentum, honestly, because of the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua, people really felt like they had a chance of throwing out the oligarchs, and ultimately, they did. At the time that this was happening, you had things like the Archbishop of El Salvador, who was murdered by a paid assassin as he was saying mass. It was such an affront to basic human values, that there was a lot of support and a lot of momentum at the time. I felt like I was part of something pretty big. It was fun to go out at night and paste up the posters all over town. I felt like I was doing my part to help the struggle.

I mean, they did end the war, both El Salvador and Guatemala and actually the FMLN (Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional) candidate in El Salvador was just elected President within the last month. So change actually did happen. And I feel like I did make a small contribution to that.

LB: So you have a lot to be proud of.

NP: Well, I don’t like to think of it that way, but I guess I am proud of making a contribution. In fact, I’m actually going to go back down there pretty soon and get reconnected because my younger son just went to college, and I’m looking back and I feel like I haven’t quite fulfilled my calling in Guatemala somehow.

LB: What do you think is in the future?

NP: I don’t know, I just think I have a lot of skills. I went on and I became an executive producer at CNN. I have a ton of connections and I have a lot of skills and I think I can help them some more. Because I think that the indigenous people are still, they’re not the minority, but they’re treated as if they were one. I’m thinking about it, I’m talking about it with some people, and I’m just not sure what the appropriate thing to do is.

LB: Thank you so much for talking to me and taking some time for this. It’s been really useful, and also, great to meet someone who gave us some of the things I’ve been going through recently.

NP: I’m so happy you’re doing this, because this is exactly what I wanted, to give them some exposure. Because, you know, these things are interesting to me, but I forget that other people find significance in them as well.