Messy Nessy Chic, May 24, 2019

May 24, 2019

Brooklyn’s Revolutionary Social Club

By Francky Knapp. Originally published at https://www.messynessychic.com/2019/05/24/brooklyns-revolutionary-social-club/

On a quiet street in Brooklyn, lies a very peculiar treasure chest. It safeguards the boots of Mexican revolutionaries, and the sound bites of rebels; it collects buttons, posters, and anything upon which one could scrawl a grassroots manifesto. It’s New York City’s “Interference Archive,” and it’s the volunteer-based library, gallery, and archive for tools of revolution past, and present. “These are the things that get thrown away,” volunteer Jen Hoyer told Messy Nessy when we dropped in for a visit. “I mean, sometimes museums just won’t know what to do with them – how do you archive a t-shirt from a protest?” What’s more, how do you make sure that t-shirt’s message won’t be forgotten in a musty storage unit? That’s where Interference swoops in like a veritable Robin Hood: unlike most institutions, everything here is 100% accessible to the public. It’s Brooklyn’s revolutionary social club.

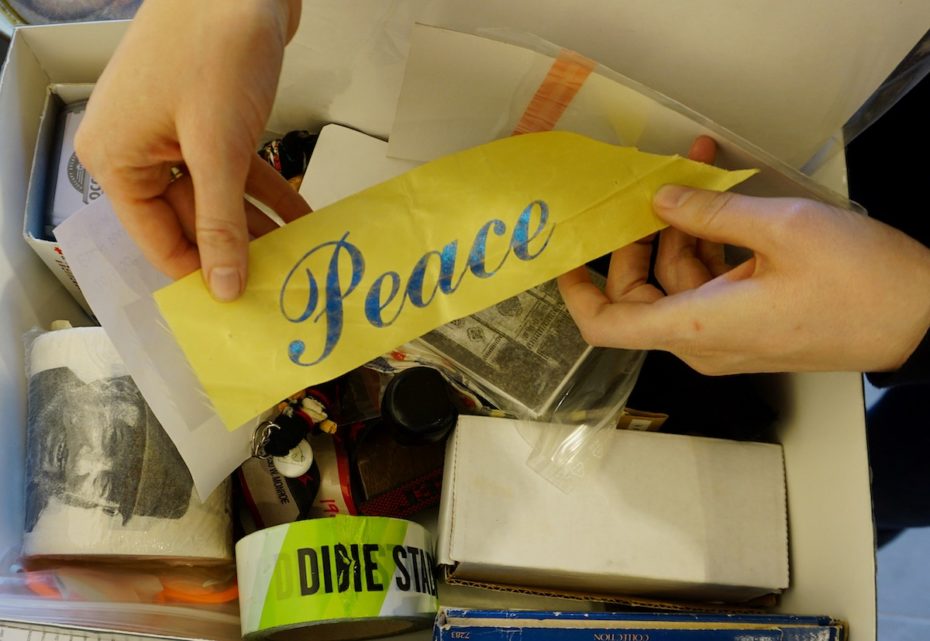

It’s a warm, sunny Sunday afternoon when we visit Interference – one of Spring’s first – but that doesn’t mean the team is taking the day off. “Is that the box from Texas?” asks Sophie to Jen, before we all sit down for a chat. “There’s a project in Texas that sends books to prisoners,” Jen clarifies. Bringing in tools that humanise prisons, and hone in on rehabilitation, is just one way to help lower incarceration rates. Of course, not everything they’re sent can be accepted – so the materials have been sent to Interference, which is a fine place to call home.

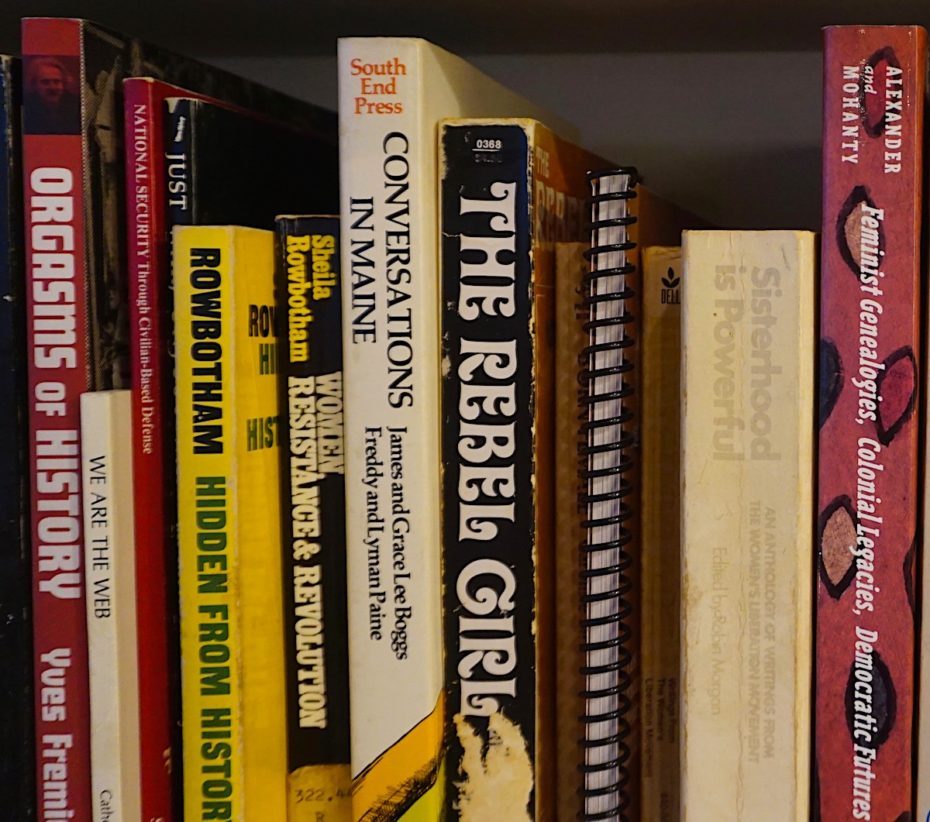

The Interference Archive was co-founded in 2011 by four people, Josh MacPhee, Kevin Caplicki, Dara Greenwald, and Molly Fair, who first came together as artists and activists of a print collective called “Justseeds”. They were gathering materials for a show at a local exhibition space called Exit Art, and realised the sheer volume of political and social justice posters and fliers they had amassed in their own apartments – to the point where people would be contacting them to do research in their homes. That reality begged the question: why on earth were these materials so difficult to gain access to in the first place? And how could they change that? The reality is, so many of these materials – fliers, posters and other materials – aren’t saved in the first place. If they do get archived, it’s usually by institutions that require academic or research credentials to be accessed. What Interference did was a game-changer, turning the idea of archiving into a social, community experience.

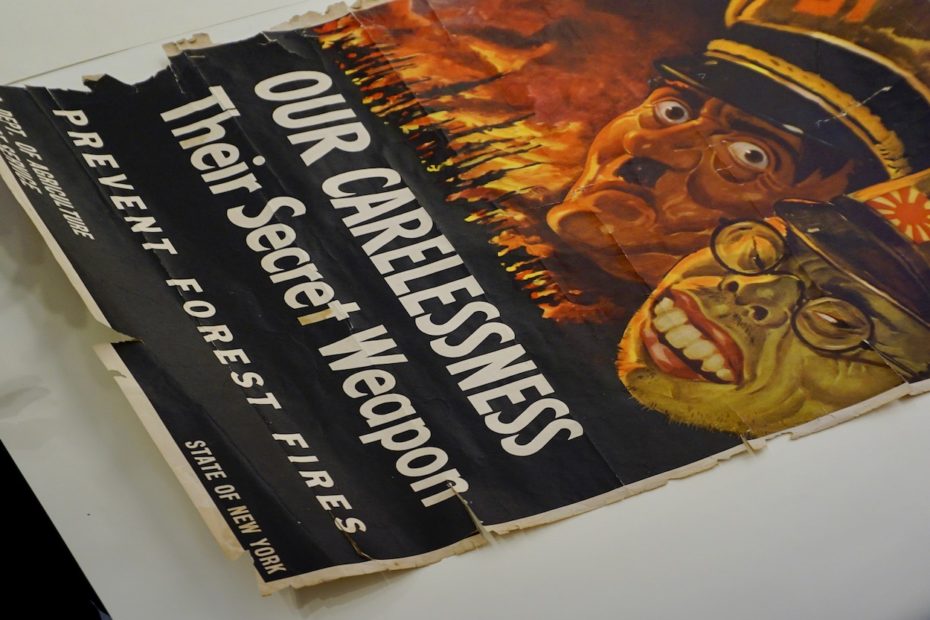

Collections are often sent in from individual donors, book stores, or movements with massive records themselves. The only thing they don’t accept? Anything too personal, that could potentially be used as evidence (ex. photos) because, remember, all this stuff is accessible to anyone. Some of the donation sources even have to remain a secret. It’s also important, says Jen, to show “the broad scope” of materials that’ve been used to stir the public, on both the left, right, and extremist sides of the political spectrum. “Want see something really crazy?” she says, and delicately pulls out one of the weirdest pieces of WWII propaganda we’ve seen, even in our many years of trawling the web: a poster with a racist caricature of a Japanese man, positioned next to Hitler’s face, above a wildfire. In this case, we see the ferocious extent to which the US government appealed to citizens’ darkest political fears when drafting something as simple as a fire safety ad.

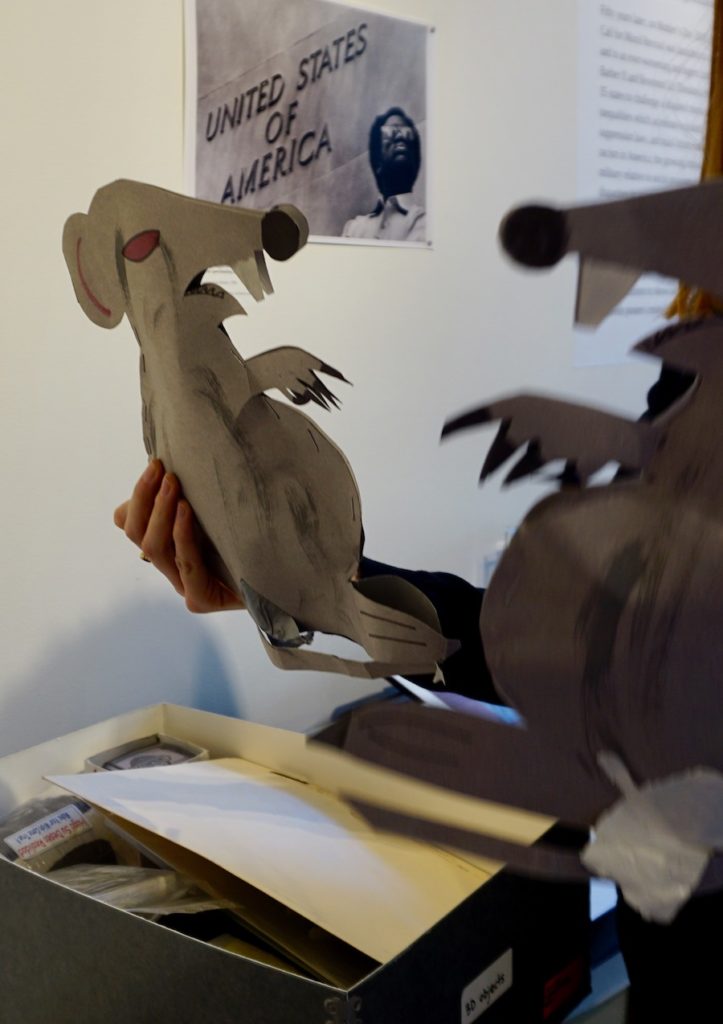

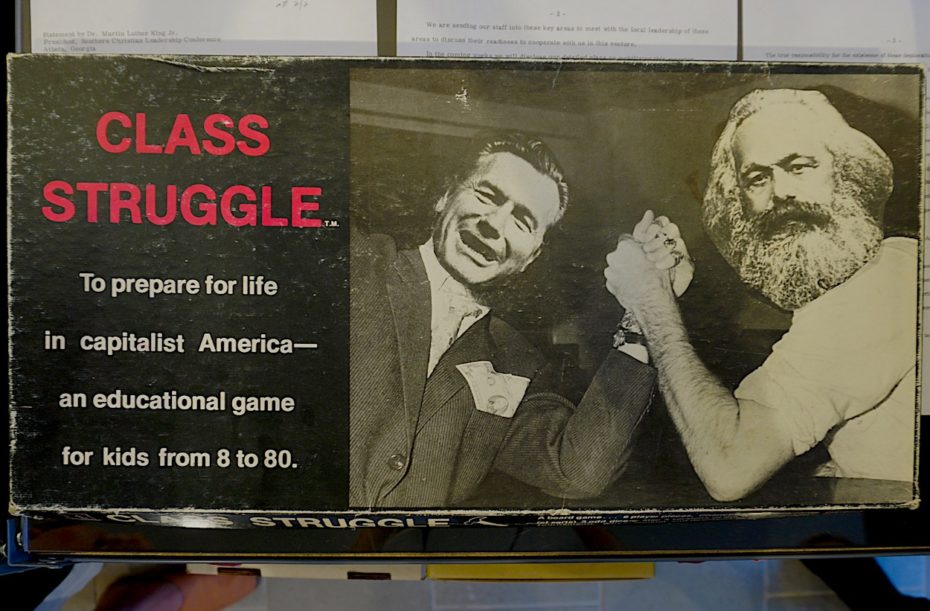

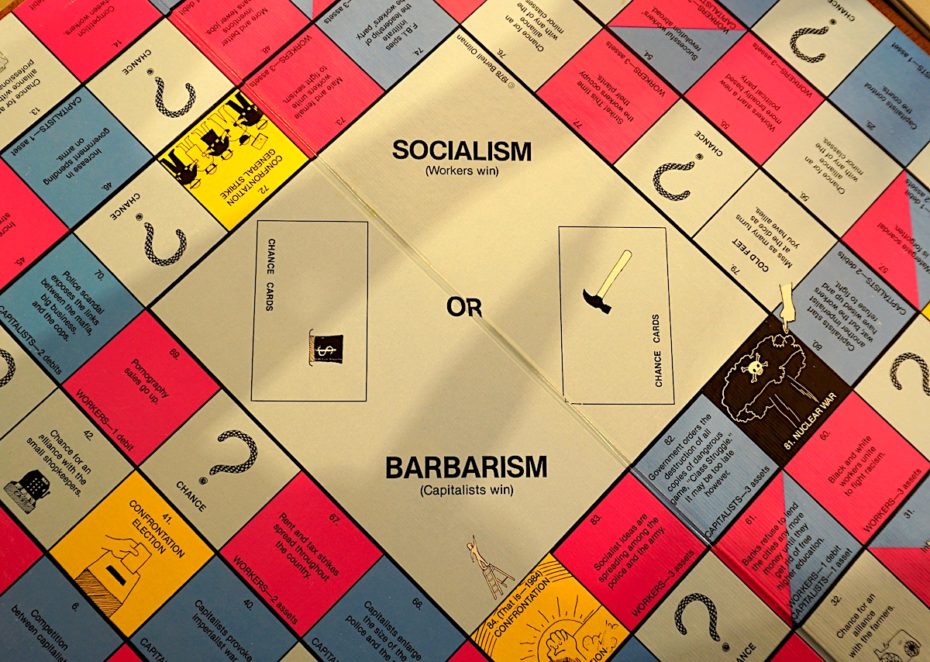

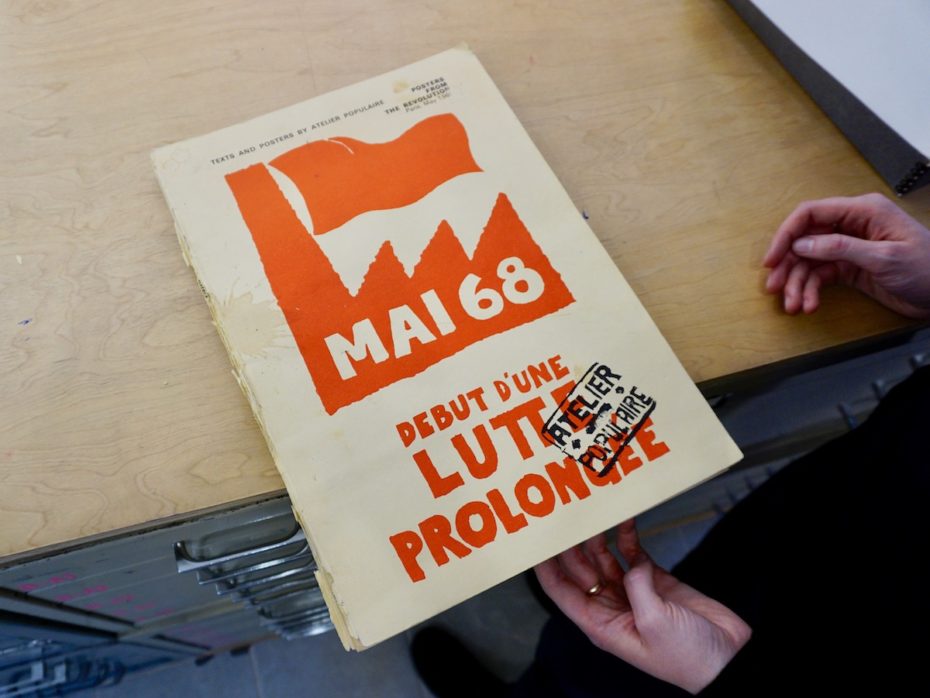

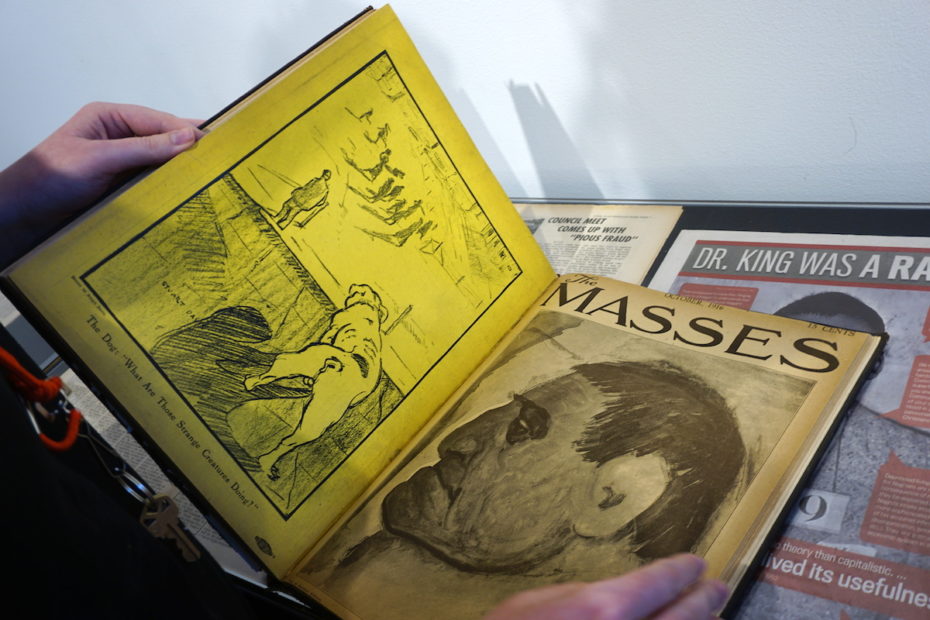

As relics of social unrest, many of the archive’s materials had to convey secret, or cryptic symbolic messages. They’re often everyday objects, like little dolls, or the arpilleras (decorative cloth squares) that Chilean sewed to declare their solidarity when they couldn’t use their voices under Pinochet. In rummaging through the archives, we come across a pair of big paper rats, which we’re told has long been positive a symbols of the union worker. There’s even a giant inflatable rat in the city that gets plopped in front of union-unfriendly businesses to call them out. Our personal favourites from the collection, and yes, we’re biased, are the beautiful graphic designs of their French posters, notably from from Paris’ 1968 student riots:

The revolution is, and has always been, graphic; from the ’68 riots, to Shepard Fairey’s iconic 2008 Barack Obama campaign poster. “The aesthetics of protest and revolution are really in vogue right now”, says Jen’s colleague Sophie Glidden-Lyon. A big part of Interference’s mission is making sure that the posters, books, fliers, pins, etc. are not only available to their communities of origin, but are actively brought into new scenarios that reignite their use, and community solidarity.

There are “Propaganda Parties”, in which artists, activists, and locals come to mingle while making buttons, stickers, posters and more for local movements and issues. They’ve even had a “Feminist Wikipedia Edit-athon” to amp up the amount representation notable ladies get on the website.

They say you’re only as good as the company you keep, and digging through the aisles of boxes, overflowing with hand-made memorabilia and dog-eared books, you can’t help but feel as if you’re amongst the best/ trusted friends. In an age where it’s easy to stay online (and hey, no shade, we’re obviously the Internet’s #1 fan) it’s a beautiful thing when one can entice those communities off the web, and into the streets. Or better yet, the social justice social club that is Interference.

At a time when when fast-activism and questionable GoFundMe campaigns are rampant, Interference Archive is a champion for making tangible, creative connections with one another – as well as carving out a place to recognize the nuances of these materials as shared, community relics. When you walk into a place that makes organising about human bonding, you build a sense of accountability. Both Jen and Sophie happen to come from archival backgrounds, but at the end of our time together, they can’t stress enough how much anyone can get involved at Interference, to whatever extent they can. Whether it’s to learn, organise, or curl up with an anarchist manifesto for a few hours, this isn’t just a place to research history. It’s a place to live it.