AIGA Eye on Design, February 16, 2018

February 16, 2018

How New York’s Interference Archive Keeps Activist Design History Alive

published here on February 16, 2018

Thousands of colorful design objects—posters, fliers, zines, stickers, books, fabric, newspapers, buttons—curl and unfurl on the shelves of the Interference Archive’s new Park Slope location. Unlike most archives, this volunteer run space, which functions as part-library, part-gallery, and part-workshop, allows visitors to take items off the shelf and page through the content. Together the pieces form a patchwork: a collectively written history of radical political movements from over the past 60 years.

The archive first began as the personal collection of Josh MacPhee and the late Dara Greenwald, who by the mid-2000s had filled their home with so much social movement ephemera that PhD students were regularly knocking on their door to do research, weaving their way around cumbersome boxes stacked high in the living room. As artists heavily involved with social justice movements, MacPhee and Greenwald had been absorbing, accumulating, and indexing the printed matter around them; gathering together material produced by an increasingly international community of politically engaged image-makers.

“I would get a package from Japan with flyers by people organizing around keeping the park public,” says MacPhee. “Then I’d get a package from England of posters about squatting. It was a kind of pen-pal network.”

In 2011, the couple teamed up with Molly Fair and Kevin Caplicki to make their collection public, moving it to a large warehouse in Gowanus. Greenwald called the space Interference Archive in order to capture “the idea that the collection causes static, or interference, in institutional archives and in the larger society.” Today, its name continues to underpin its ethos: The library functions around the idea that allowing the public to physically engage with radical material keeps radical thought alive, and that ephemera from the past can inspire new iterations of long-held movements.

It’s this unique ideology that has made the Interference Archive not just a place for research, but the subject of research, too: PhD students now knock on the door not simply to look at the material, but also to write papers on the ins-and-outs of the library.

This winter, after being displaced from the Gowanus warehouse, the archive reopened as a storefront just off 5th Avenue in the nearby Brooklyn neighborhood of Park Slope. Inside the airy, brightly-lit new space one might find, for example: A full set of ’80s Guerrilla Girls posters; a collection of Cuban publications, designed to show solidarity for people of Africa, Asia, and Latin America; an extensive selection of The Black Panther newspaper; buttons made by students in China; queer zines from Poland; signs calling for liberation from third-world countries. All readily available be touched, thumbed through, and read.

It’s here at the Interference Archive, amongst stacks of boxes, that new graphics, slogans, and designs are spun from a history still in the making.

A pollinating knowledge base

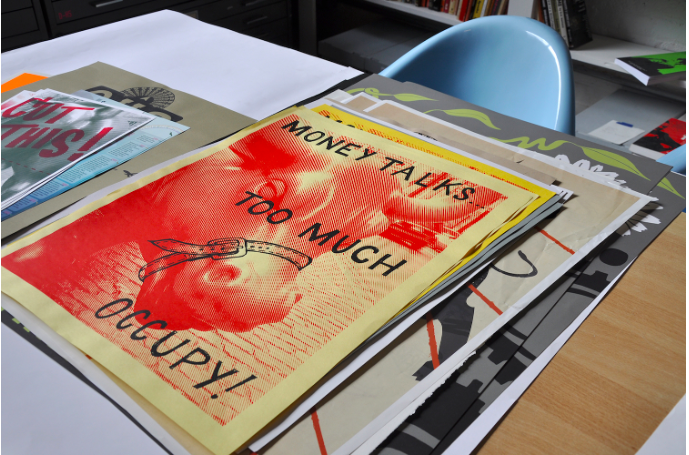

It was shortly after the collection first opened its doors that the Occupy Wall Street movement began to gather momentum, providing the library’s founders with motivation as they observed a real need among Occupy participants for information about social activism’s past. In turn, the library began collecting reams of material generated by Occupy, from carefully arranged, bright orange screen prints to hand scrawled fliers covered in Sharpie. Today, this extensive collection regularly draws those writing the history of the movement to the library’s stacks.

Seven years down the line, and the archive has also hosted numerous exhibitions based of its collections—shows with names like Armed By Design: Posters and Publications of Cuba’s Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America and RadioActivity! Antinuclear Movements from Three Miles Island to Fukushima. The exhibitions have spurred books, events, and graphic workshops, and volunteer and member numbers have rapidly grown. It’s in this way that the Interference Archive is more than an archive; it’s a community space, and a hub for discussion, making, and organizing.

Although the physical location has recently changed, the ideology underpinning the way the collection is arranged hasn’t. The library has always been ordered by material rather than the standard archive practice of organizing by donation; posters go with posters and newspapers with newspapers, for example, and within these sections the archives are arranged by theme, date, or movement.

Crucially, emphasizes MacPhee, this method ensures that the collection is arranged by how people actually use it. Few of the archive’s many thousands of items have been digitally indexed, and it’s likely to stay this way: the physical process of pouring over items espouses the kind of serendipity the Interference Archive likes to promote. Long-time volunteer Monica Johnson describes the enjoyable “scavenger hunt” involved for a volunteer who’s fielding a specific request: together with the visitor, they’ll have to scour the shelves, discovering unexpected finds along the way. “It’s a great situation because we create this relationship with others that is equal, as opposed to me being the authority and the resource,” she says.

“One of my favorite things that happens here is that, because there is still the analog mechanism for finding things, people coming looking for A then find B, which sits next to A, which they would never have found using an internet search,” adds MacPhee. “It transforms how people think about what they’re working on, because they’re like, ‘I didn’t even know this existed.’”

Preserving by activating

In any given week, half a dozen donations turn up at the archive’s door. They range from small envelopes with two to three items inside—maybe a leaflet, or a home-printed poster—to a mysterious 2×3 cardboard box that shows up by UPS. “We’ll pop it open, and it’s an entire box of Marxist journals from the 1970s,” says MacPhee. “We’re like, ‘Whoa!’”

“The interesting thing is that people who tend to donate their possessions are ones who have been intentionally not donating those possessions to elite academic institutions or traditional archives, because of the barriers to accessibility,” says Johnson. “This place functions by the idea that preserving ideas and preserving histories comes by activating them.”

In that way, the Interference Archive interprets preserving not simply as encasing something behind protective glass, but instead as allowing people to touch, rummage, and leave their fingerprints all over it. Hidden away unseen, a work is more likely to be forgotten; seeing and conversing with an old object keeps it alive and pertinent.

“If you want your legacy maintained for posterity’s sake, this may not be the place to donate.” says MacPhee. “If you want 14 year olds pawing through your poster collection, then this is the place.”

Networks extending

To activate means to keep alive; to spin content into new contexts; to draw parallels between the past and the present. It’s to initiate, animate, and energize.

At Interference Archive, activating goes beyond having an open-access collection; it includes producing bi-weekly podcasts that bring stories to the surface, and organizing a continual rotation of exhibitions, which find new frameworks for looking at activist history through a contemporary lens. The library also encourages volunteers to shape the programming: when Johnson first got involved, for example, she co-curated an exhibition of political comics, Our Comics, Ourselves, which has been touring the U.S. since it first ran—lifting the collection’s material even further out from the confines of the archive’s walls.

Along with a group of volunteer mothers, Johnson has also started a series called Radical Playdates, inspired by wanting to volunteer but not having the time or resources. Parents can come and spend time with the collection while their kids engage in a selection of books and toys that relate to social movement history.

Perhaps one of the greatest ways that the Interference Archive continues to activate its graphic materials, though, is through regular making events, which it playfully calls “Propaganda Parties.” When there’s a big protest happening in New York, the library will host a Propaganda Party a couple of weeks ahead of time for people to make signs, posters, patches, and buttons—using processes and imagery informed by what’s around them in the collection. A long table will be stacked with button making machines, colorful card, and thick marker pens; another with a massive roll of fabric for screen-printing, where people paste orange paint onto boards, cutting out prints like an assembly line, making patches from the fabric by pinning chopped-up squares onto clothes with punkish safety pins.

Ahead of the 2017 Women’s March, around 1,000 people filled the former warehouse in Gowanus—ages ranging from small babies and teenagers to young adults, parents, and grandparents. High schoolers spent hours glued to the button tables, with local Brooklyners surrounding the proofing press to make reams upon reams of posters. MacPhee and Johnson describe the atmosphere as buzzing and uplifting, an inspiring coming together and creative exchange.

“At the March, we then saw the posters from the party everywhere, in windows and on the street. People were taping them onto cardboard, cutting them up and putting them all over the place,” says Johnson. “We also saw ‘re-drawings,’ where people re-sketched versions of the designs from the party that they were spotted in the protest.”

It’s in this way that the Interference Archive promotes and inspires linage. What’s in one box informs a new graphic, a new sign, a new slogan, which gets held up in a crowd and then copied, recycled, and revised by others, a scrap of which might later get placed into an envelope and slid under the door of small storefront in Park Slope. There, it might get picked up by a volunteer one morning, and added into a box with a cornucopia of other urgent, colorful prints.