Comics Beat, January 29, 2016

January 29, 2016

Originally posted at http://www.comicsbeat.com/on-the-scene-our-comicsourselves-illuminates-the-history-of-comics-diversity/

On The Scene: Our Comics, Ourselves Illuminates The History of Comics Diversity

01/29/2016 By Charles Brownstein

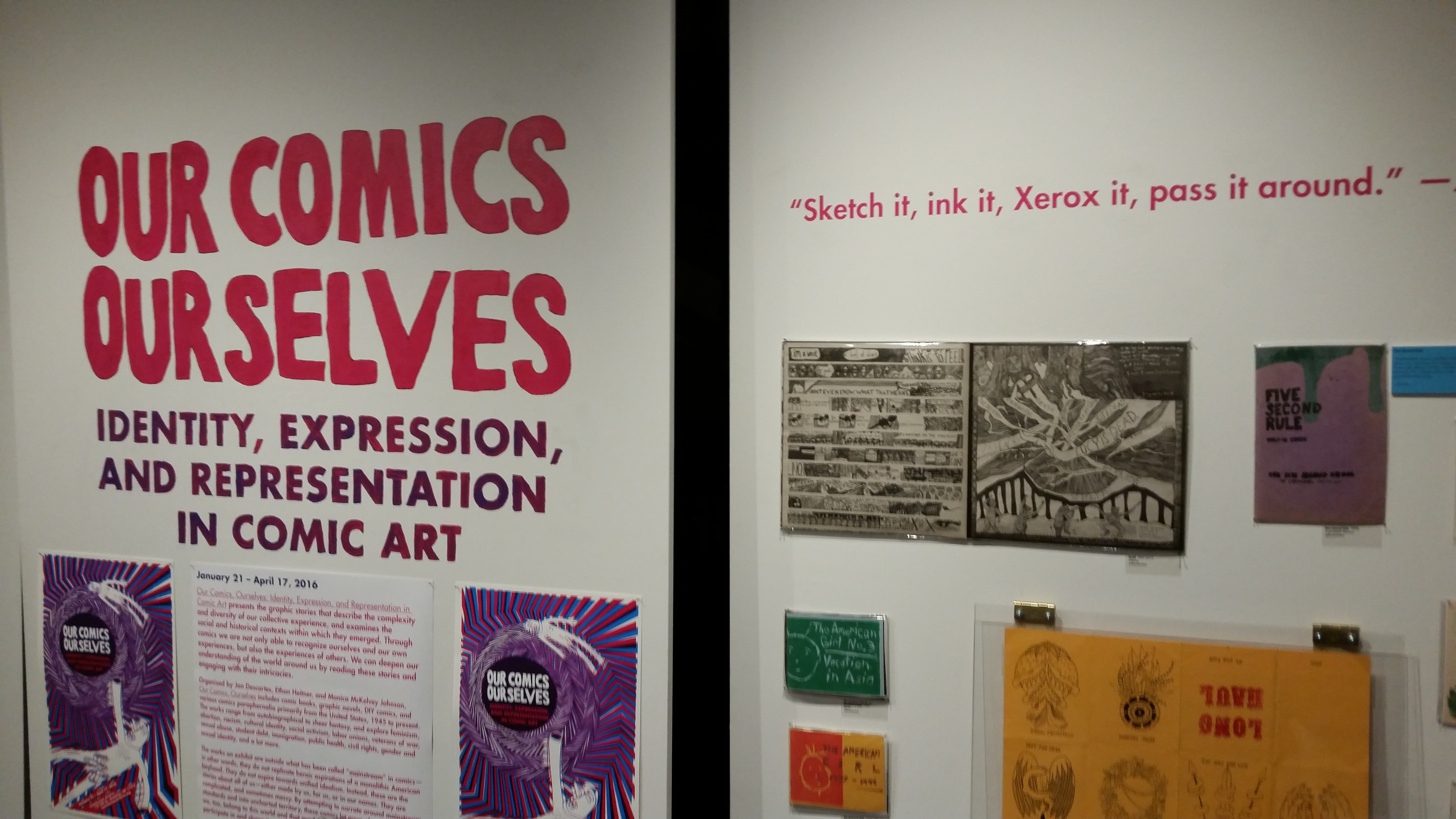

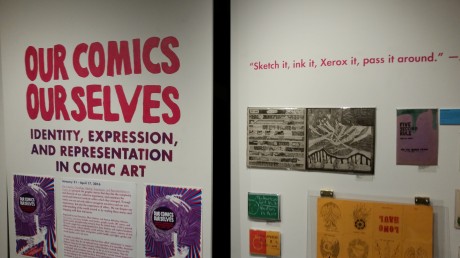

New York was slowing down in anticipation of the winter storm, but that didn’t stop plans for Interference Archive’s Our Comics, Ourselves opening last Thursday night. Nestled into a grudgingly gentrifying block of warehouses and auto body shops on 8th St in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood, the Archive’s lights were a welcoming beacon in the otherwise frozen night. The exhibit within provided a robust survey of the history of diverse representation in comics, shining a long overdue spotlight on a heritage that will no longer be left out in the cold.

Organizers Jan Descartes, Ethan Heitner, and Monica McKelvey Johnson gathered a broad, well-considered, and cohesive overview of comics whose authors, characters and subject matter spoke to the concerns of diverse audiences. While much of the work on display was visually pleasing, aesthetics wasn’t the primary objective here, storytelling was. The works on view spanned back to 1939, with large concentrations of material from the Underground Comix movement, contemporary graphic novels, and mini-comics. The original printed artifacts took center stage, with viewers invited to study selected pages on the gallery walls, handle physical copies of various books and mini-comics, or read full texts on the gallery’s iPads.

There were several smart content threads in the exhibit, fleshed out by editorial contributions from Elvis B. Paul Buhle, Hillary Chute, Leela Corman, Edie Fake, Carol Tyler, Sophie Yanow, and a dozen other experts and practitioners. A companion catalog currently available from Interference Archive contains brief essays from these contributors delving into their personal relationship with the works on view in the show.

The exhibit opened with a display of mini-comics, emphasizing the format’s ability to provide a low barrier to entry, and as a consequence, a broad range of personal expressions. A table filled with dozens of mini-comics was set up for visitors to browse, while examples of contemporary work by Edie Fake, Juliacks, and Ines Estrada shared wall space with contributions dating as far back as 1972. The comics set up for browsing ranged from crude photocopied pieces to carefully silkscreened productions, with subject matter including autobiography, activism, and even a handbook for saving people O.D.’ing on hard drugs.

Los Bros. Hernandez’s Love and Rockets anchored a wall devoted to the three-dimensional presentation of feminine identity and personal power. Appreciations by A.K. Summers and Sandy Jimenez praised the series for, in Jimenez’s words, “telling stories about people who’ve been on this continent for centuries and are still marginalized today.” Beneath the Hernandez selections, was a small cluster of Wonder Woman images: the inaugural 1972 issue of Ms. Magazine; Wonder Woman #203, the Samuel Delany penned “women’s lib issue;” Trina Robbins’ & Kurt Busiek’s The Legend of Wonder Woman #1 from 1986; and a 1979 issue of anarchist newspaper Black Flag, satirically merging Margaret Thatcher and Wonder Woman. The Wonder Woman images identified the influences Los Bros. simultaneously celebrated and subverted, while also providing examples of how mainstream comics’ feminist expressions interacted with the popular culture.

Moving backwards in time, the next display showcased the heritage of women’s comics anthologies, starting with Trina Robbins and Barbara “Willie” Mendes’ It Ain’t Me Babe from 1970, and Wimmen’s Comix, which spun off of that first publication. A copy of Lee Marrs’ scatologically subversive The Compleat Fart was presented, along with Joyce Farmer & Lyn Chevely’s anthology Tits & Clits from 1972, Aline Kominsky-Crumb & Diane Noomin’s Twisted Sisters, and 1990s publications Girl Talk, Diva, and Real Girl. These comics by and about women responded to the spirit of their times, provided outlets for some extraordinary talent, and stood as counterpoint to historical male dominance in both mainstream and alternative comics.

Turning the corner, the next wall showcased contemporary feminist voices, placing work by Cathy Guisewite beside Julie Doucet, Kelly Sue DeConnick & Valentine DeLandro, Phoebe Gloeckner and others. These selections identified a school of women’s comics that stridently emphasize the expression of feminine concerns as its own virtue. Adjacent to this display was a selection of comics “in defense of women’s health and sexual freedom” that included Joyce Farmer & Lyn Chevely’s post-Roe v. Wade educational comic Abortion Eve; Leah Hayes’ Not Funny Ha-Ha, Sheri S.Tepper & Gary Barnard’s 1974 mini The Perils of Puberty, Carol Tyler’s “Anatomy of a New Mom” t-shirt, and Leela Corman’s heart-wrenching PTSD: The Wound That Never Heals.

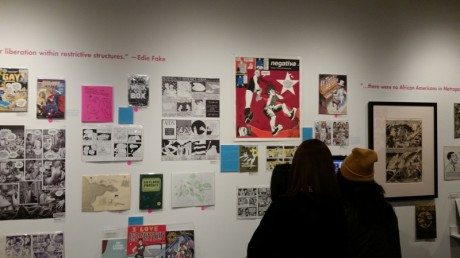

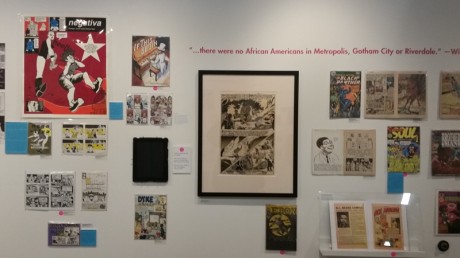

Queer representation covered the next walls. Works included the Howard Cruse founded anthology Gay Comix, Wuvable Oaf by Ed Luce, Mary Wings‘ 1978 Dyke Shorts, Edie Fake’s Gaylord Phoenix mini-comics, A.K. Summers’ Negativa, as well as early mini-comics editions of Diane DiMassa’s Hothead Paisan Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist, and collections of Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For. The comics in this section developed along a parallel track to the women’s comics showcased elsewhere in the exhibit, but set themselves apart as steeped in the local and cultural milieus that informed queer culture from the 1970s through the present, most especially the syndicated works from Bechdel and Cruse.

Hazel Newlevant’s 2013 mini-comic If This Be Sin, chronicling the life of Gladys Bentley, the butch lesbian pianist and singer who performed in drag during the Harlem Renaissance provided a bridge to the exhibit’s segment on African American representation. Led off by an original page from Larry Fuller’s 1970 underground Ebon, this section included Grass Green’s Super Soul Comix; Guy Colwell’s Inner City Romance; the Sims Brothers’ Brother Man; mid-70s comics featuring the superheroes Black Panther and Black Lightning; a spread from golden age All-Negro Comics #1, and Soner On’s 2011 black interpretation of Richie Rich. This section was the thinnest within the exhibit, and was the only segment of the show where I thought notable omissions occurred. Where are C. Spike Trotman, Jimmie Robinson!, and Ron Wimberly, three of the today’s more notable and prolific creators of color developing strong comics work that speaks to race? Where were Milestone Media, ANIA, Real Deal, Dwayne McDuffie, and Turtel Onli? Even here, however, identifying a list of omitted creators doesn’t diminish the exhibit’s point about how black content stands apart from the mass of comics in both mainstream and alternative realms, and how much further comics has to go to achieve fuller representation of African-American authors and culture.

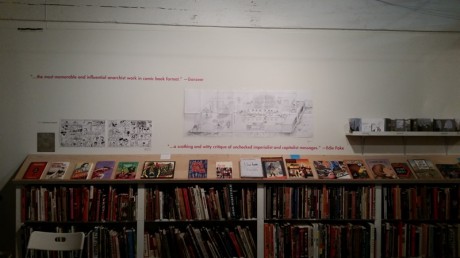

The gallery’s final wall gathered comics addressing incarceration and war, with examples that included Ben Martin’s 1939 anti-war polemic John Black’s Body alongside Palestine, Barefoot Gen, Real War Stories, Jess Ruliffson’s Invisible Wounds, examples from The Real Cost of Prisons Comix, and others. Down the hall, the exhibit continued within Interference’s archive room and library. This room included a wall showcasing World War 3 Illustrated, and a section on police abuse that included the comics Channel Zero by Brian Wood, Warren Ellis and Darick Robertson’s Transmetropolitan, New York’s Killer Kop Komix, with contributions by Fly and Seth Tobocman, and Sophie Yanow’s War of Streets and Houses. Finally, there was a display of several essential graphic novels that spectators were invited to browse set out beneath original art from Eroyn Franklin’s Detained.

What I liked best about this exhibit is that it emphasized the importance of what the comics had to say above all. Corporate work sat beside hand-made small run xerox comics. The ideal was comics as a medium for communicating ideas of social value to peer communities. It was very well done. It engaged the content and the creators with an eye to showcasing the work that is the change we want to see, rather than creating a parade of outrage or schadenfreude about the errors and omissions of large corporations. It was a street level exhibit that encouraged engagement with the content, and invited the viewer to seek out more, and to tell their own story.

Interference Archive is located at 131 8th St. in Brooklyn, convenient to the F, G, and R trains at 4th/9th Street. Our Comics, Ourselves is on view at Interference Archive through April 17, with upcoming events featuring Leela Corman, Hilary Chute, and more. For more information, visit: https://interferencearchive.org/

Charles Brownstein is the Executive Director of Comic Book Legal Defense Fund