Brooklyn Rail, November 2, 2017

Published on April 24, 2024

Resistance Across Time: Interference Archive

by Andreas Petrossiants

Originally published at http://brooklynrail.org/2017/11/artseen/Resistance-Across-Time-Interference-Archive

PAUL ROBESON | SEPTEMBER 20 – FEBRUARY 18, 2018

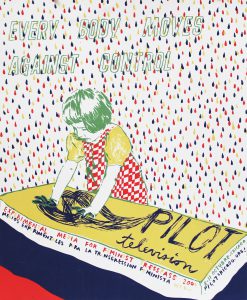

In a review of the Met Breuer’s Delirious: Art at the Limits of Reason, 1950-1980, Emily Watlington convincingly argues that our “delirious times” call for responsively delirious curation.[1] As buzzing news alerts stoke excess trauma through an ascendant reactionary (neo-) conservatism, such a call is not off-mark. However, Evonne M. Davis provides a stellar curatorial counterpoint with the exhibition Resistance Across Time: Interference Archive at the Paul Robeson Galleries at Express Newark. The show presents a chronological parsing of social activism—with keen attention to feminisms from various historical moments and locations—via a selection of posters from Brooklyn’s Interference Archive. Founded in 2011 from the personal collections of the late Dara Greenwald and Josh MacPhee, the archive includes materials from African and Latin American liberation movements, anarchist posters from the United States, and ephemera from European squatter movements, to mention just a small and varied segment.

In the Paul Robeson Window Gallery section, a glass vitrine recalling storefront window displays invokes the building’s past as a mid-century department store. (Anonda Bell, director and chief curator of the gallery, mentioned to me that this setup recalls a less-than-famous event when Duchamp installed a window display in a nearby store, publicizing the translation of his first monograph into English in 1959.) There, an anonymously authored print from 2000 pictures a woman pointing a gun in the direction of the spectator, slightly off target as if the enemy creeps behind us. Circumnavigating her is the mission statement: “We will defend our ability to choose.” Below, a further declaration: “Keep your laws off my body.” In the first statement, there is the invocation of unity implied by the communal “we.” In the second, the anonymous print-maker supplies activists and allies alike with a rallying-cry. This dual-proclamation enunciates the exhibition’s two complementary goals: a summarizing of activist histories, and an invitation to get involved in the struggle that continues—to look in the direction of the pointed gun, as it were.

The selection of posters spans forty years of protest: a small sliver from the accessible stacks of the completely volunteer-run Interference Archive’s collection of posters, prints, books, zines, buttons, and other materials. Importantly for the community it serves and fosters, the archive operates on a “scholarly” level producing exhibitions, publications, and the like, and on a civic level generating the conditions and site for an activist community through their materials and community—oriented screenings, talks, and workshops. The latter function is underlined by the archive’s role as a “site of production” and as a “toolbox,” per Gregory Sholette. As he describes, their lack of institutional support allows them “to achieve the highest level of political and economic autonomy possible given the less than ideal circumstances of contemporary life.”[2] As Greenwald remarked at the 2009 Creative Time Summit, her long-term goal was to “make resistance visible”—something this off-site exhibition extends into a different community and context.

The archive’s international and trans-historical scope is underlined by works such as Solidaridad con las Costureras de Guatemala (1992), by the US/Guatemala Labor Education Project and artist Marilyn Anderson. The poster includes the direct provocation: “Was your shirt made by Guatemalan women earning $3 a day?” To the left are two prints by the Guerilla Girls. The text of the poster Relax Senator Helms, The Art World IS Your Kind of Place (1989) mocks gender inequity in the art world in tandem with notorious conservative culture warrior Senator Jesse Helms: “Women artists have their place: after all, they earn less than 1/3 of what male artists earn.” In the wake of the last election, there has been a corresponding intensification of intra-Left blame-casting: those who mistakenly accuse identity politics for ostracizing an aggressive disenfranchised working class, and others who condemn labor movements for ignoring the oppression of women, people of color, and LGBTQ communities (clearly, all laborers as well). Concurrently, a memetic reactionary Right has usurped traditionally Leftist methods of publicity and protest to blame the mitigated cultural liberalization of recent decades for the traumas induced by economic neoliberalism—as Sabine Hark and Sighard Neckel recently discussed in Texte Zur Kunst. Davis’s curatorial move is a renewed and well-maneuvered call for intersectional thinking. In positioning Relax Senator Helms alongside Solidaridad con la Costureras de Guatemala, Davis identifies the junctions between the class and feminist struggles—between the Guatemalan women workers and the overarching systems of oppression by a global capitalist patriarchy. Accordingly, Rachel Romero’s lithograph of a militant young woman in a black hat, produced in the San Francisco Poster Brigade in 1981, bears the caption: “…And the workers, they claim, are content.”

As Resistance gracefully shows, many different aesthetico-political positions and formal methodologies have been employed in the long arc of progress documented here in the cultural production of activist groups. Similarly, Georges Didi-Huberman’s exhibition Soulèvements (Uprisings) at the Jeu de Paume last year demonstrated a cross-generational presentation of resistance via a semiotic reading of “rising up.” Pertinently, Judith Butler remarks in the Soulèvements catalogue: “All the uprisings failed, but taken together, they succeeded.”[3] Perhaps, an appropriate way of adding to this sentiment here might be to say that a familiarity with the rich history of resistance is key to activating a present intersectional opposition. As Davis’s exhibition strives to make clear, we should continue uprising above and alongside those who came before us, and that Interference Archive is a valuable site/collection from which to start learning the histories irrevocably bound with the potential for victory.

Notes

1. Emily Watlington, “Delirious: Art at the Limits of Reason, 1950-1980,” Mousse, no. 60 (October-November, 2017), 178.

2. Gregory Sholette, “Interference Archive,” Entry Points: The Vera List Center Field Guide on Art and Social Justice, No. 1 (New York: Vera List Center, in collaboration with Duke University Press, 2015).

3. Judith Butler, “Uprisings,” in Uprisings (Paris: Jeu de Paume, 2016).