Culturestr/ke: Taking Back Chinatown, December 20, 2013

Published on April 17, 2024

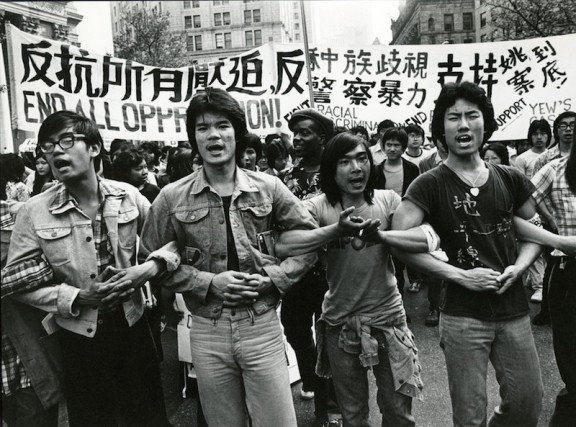

“Peter Yew Police Brutality Protests,” by Corky Lee. 1975

By Michelle Chen

On a typical day in Manhattan’s Chinatown, the streets hum with the bustle of sidewalk vegetable markets and the idle prattle of wrinkled elders—a subdued but gritty din that seems to never change. But 40 years ago, these same streets were buzzing with revolutionary fervor. Chinatown had begun a demographic pivot from an enclave of mostly older male laborers to a vibrant ethnic community of first-generation immigrant families. And when some young idealists trickled in, the social mix catalyzed a movement that went on to defy stereotypes, census labels, and borders. A new exhibit at the Interference Archive, a library and gallery space devoted to social movements, located in the Brooklyn neighborhood Gowanus, highlights this obscure page of the neighborhood’s history— sandwiched between the Bachelor Society and the Model Minority—when the new wave of Chinese Americans found their political stride and began re-imagining themselves and their community.

Serve the People, a one-room exhibition, revisits the cultural turn that branded New York’s Asian America as an overlooked moment in New York and Asian American political histories. The collection features posters, publications and leaflets, much of it donated by the Museum of Chinese in America, that are both crude and wildly imaginative.

A Warhol-esque pastiche of women warrior figures in a poster advertises a performance of the “Bok Choy Blues,” which the viewer can only guess was a mash-up of folk and contemporary genres. Some of the more formal political journals, like the nationally circulated “Bridge Magazine,” and the local newspapers like “Workers Viewpoint” broadcasted slogans of Third World class struggle. Published in English (presumably for a U.S.-educated readership), the essays exhort Chinatown residents to join the Young Lords and other movements on a global anti-imperialist front.

Bridging the Mekong and Mulberry Street, this new cultural vanguard was fueled by postwar migration trends and New York’s deep legacy of urban civic agitation. In Chinatown’s winding streets and dingy basements, student activists, self-styled Maoist militants, and community organizers came together to spawn new media outlets and organizing campaigns. The hive of this activity was a community space on Catherine Street called Basement Workshop, where people gathered to produce literature and art and to exchange ideas. They gradually fashioned a movement culture that fused nascent identity politics with an ethos of militancy, battling on behalf of a poor, politically marginalized neighborhood.

“At the time, people were really trying to invent the idea of Asian American and understand what an Asian American identity could be, based on politics,” said curator Ryan Wong at a recent gallery talk. Prior to the late 1960s, when Asian American leftist youth activism emerged in California, there was little sense of solidarity across the different ethnicities that constituted the Asian American populace at the time (mainly of Filipino, Japanese, and Chinese descent). The media and political establishment might lump these groups under the condescending umbrella label of “Oriental,” but Asian American movement activists were on a mission to brand a truly pan-Asian identity, equal parts American and Third World. The Asian American identity, Wong said, was a vehicle for young activists “to challenge how we’re seen in America and how we see ourselves,” through self-produced print and visual art, along with other cultural productions like theater and dance.

The Basement Workshop’s artistic renderings of Asians in America complemented their activism in the community, as activists organized unprecedented mass demonstrations and street fairs. The graphics activists used to represent the movement often cleverly re-appropriated Orientalist tropes, like Chinese characters or dragon images, and glossed them with postmodern design elements. Japanese American artist Tomie Arai’s iconic “Wall of Respect” mural centered on a classic depiction of the Great Wall but festooned it with images that celebrated immigrant families and narratives of workers’ struggles.

In feminist publications (which arose as a counterpoint to the male-dominated activist scene of that era of the left), Asian women were depicted with depth, whether as factory workers or guerrilla fighters—a fierce rebuke to the usual two-dimensional exoticized caricatures of Asian femininity. At the time that she and her fellow artists and writers created the seminal anthology Yellow Pearl—drawing on archival photographs and other early feminist publications as templates—Arai said, “There were literally no images of Asians in America that were positive. So the whole premise was to try to create these sort of positive images that would accurately reflect our own voices.”

The movement’s agit-prop materials tended to be simpler and ad-hoc, made for hand-to-hand mass distribution. Still, the leaflets and political missives grafted a New Left media vernacular onto a rising cultural touchstone: a new Chinese diaspora that braided strands of global and local activism. In one essay denouncing Chinatown’s lack of decent jobs, social services, and housing, the Getting Together newspaper (published by the local Marxist collective I Wor Kuen) argues, “It’s as if we Asians (Chinese) in Chinatown are living in a colony controlled by foreigners (the rich, outside whites). In fact, Chinatown is not only a ghetto, but a colony of sorts.” The Basement Workshop’s do-it-yourself sensibility—and the visceral excitement of constructing solidarity through art and street action—engendered a platform to explore concepts of racial politics, gender, and community change. “I really felt like it was a very fertile time for young people to think about how to build an entirely different culture that reflected their own politics,” Arai said. “The work that you see here, I think, really is an extension of that optimism, that we could all become engaged in building something entirely new.”

The Workshop eventually disbanded in the 1980s. But its short career seeded an enduring political industry that ultimately helped crystallize Asian American activism and enable subsequent generations to articulate their community’s history and social experience, on their own terms. Chinatown’s “unofficial photographer laureate,” Corky Lee, rounded out the exhibition with a collection of his black and white photographs of various demonstrations and gatherings, many of which he helped organize.

Standing by a portrait of a steely woman holding a “Minorities Unite” poster, Lee recalled that he and fellow activists started taking pictures informally. “We were producing slide shows about events that took place, anti-war stuff … things of that nature,” said the scruffy-haired, now-middle-aged movement elder. “So we compiled all this, and we called ourselves Asian Media Collective.” Today, Lee’s archives remain some of the only documentation of Chinatown’s early protest campaigns

against racial violence and police oppression, community health fairs (which later developed into the neighborhood’s main clinic), and rallies demanding local jobs for Chinese construction workers (which eventually enlisted community members to build Confucius Plaza, Chinatown’s flagship public housing project).

Although, as a young activist, Lee’s focus was always the Asian American leftist scene, in retrospect, his attitude toward the community reminds him of an earlier political experience—a memory of his immigrant father’s viewpoint on a different, wholly American movement. When he was a young boy, he recalled, his father jarred him with prescient words: “’You know that guy, Martin Luther King? He’s gonna help Chinese.’” It sounded ridiculous to Lee at the time. But within a few years of the March on Washington, he found himself swept up in a wave of civil disobedience led by his own people—a movement following the path that the black freedom struggle had blazed for all

communities of color.

Chinatown today is no longer a hotbed of Marxist insurgency. The first flash of radicalism has long since faded, migrating to college campuses and other neighborhoods. But in Lee’s photographs and the Basement Workshop’s dog-eared prints, the Asian American movement’s coming of age remains suspended forever in its polyglot ephemera.

This article was originally published at http://culturestrike.net/taking-back-chinatown