Exhibition Dates

May 21, 2022

September 5, 2022

Opening

May 21, 2022

3:00 PM - 7:00 PM

Our Streets! Our City! explores various struggles over public space in New York City since the 1960s, and engages with past and contemporary strategies used by activists to reclaim or reimagine urban infrastructures. This exhibit is a tribute to those who have resisted top-down city-planning processes; its purpose is to honor collective fights against displacement, privatization, and municipal overreach in NYC.

¡Nuestras calles! ¡Nuestra ciudad! explora diversas luchas que desde los años sesenta se libran en torno a los espacios públicos de la ciudad de Nueva York. Además, revisa estrategias, tanto pasadas como presentes, utilizadas por activistas para reclamar o reimaginar infraestructuras urbanas. Esta instalada es un tributo a quienes han resistido procesos verticales de planeación urbana; su propósito es honrar las luchas colectivas contra el desplazamiento, la privatización y los abusos municipales en la ciudad de Nueva York.

Curated by:

Nora Almeida

Josh van Biema

Rachel Jones

Marco Lanier

Maya Chang Matunis

Lana Pochiro

Hallel Yadin

Translation: Gaby López Dena

Original Illustrations: Sophie Holin

Audio Collages: Rachel Garber Cole

This online exhibition provides a glimpse of the material on display. Please join us at Interference Archive to see the full exhibition. Pick up a copy of the publication accompanying the exhibit to learn more about struggles for housing, food, and street justice. The book features reproductions of ephemera and original illustrations by Sophie Holin–it’s available for purchase at the archive or you can order a copy online.

Interference Archive and this exhibition are living collections. The exhibition was created from material housed at Interference Archive, and there are gaps in this story. We would love to hear from you if you have stories or material you want to share. If you’d like to learn more, please get in touch at info@interferencearchive.org.

Food Justice

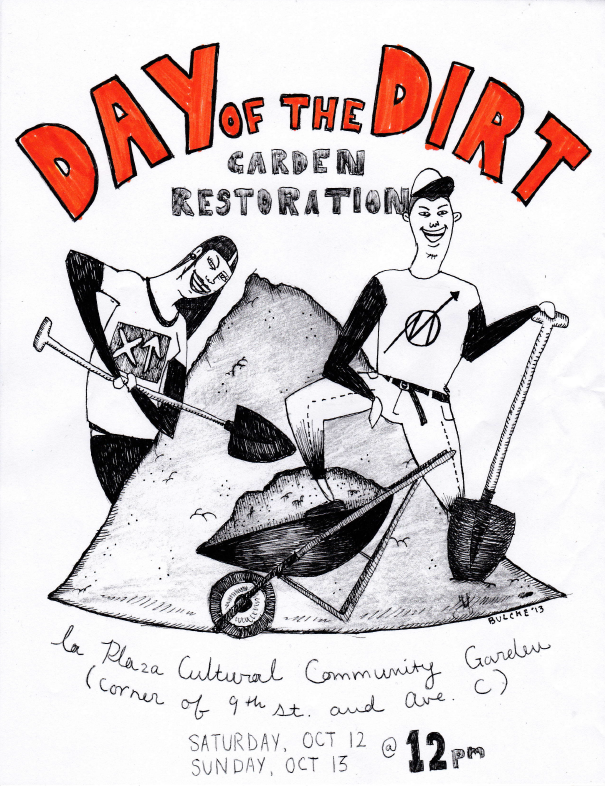

During the 1960s and ‘70s, widespread neglect of public space and infrastructure created fertile conditions for the community gardens movement. From the Bronx to the Lower East Side, people came together to transform untended lots, without permission or assistance. Many gardens were created by Black or Latino activists to grow fresh food and provide social spaces for their neighbors.

Some gardens—like El Jardín del Paraíso, created in 1981 by Puerto Rican residents on the Lower East Side, and the still-autonomous Hattie Carthan Community Garden, created by Black youth in Bedstuy in 1991—continue to thrive thanks to years of hard work by grassroots organizers. Other gardens struggle with increased municipal control by city agencies, and some have become casualties of gentrification and development.

In the fight for a greener NYC, groups like the Green Guerillas, Bread and Puppet Theater, Public Space Party, and Earth Justice used diverse tactics from street parades and civil disobedience to seed bombing.

Food justice activism is not limited to community gardens. Food insecurity is an ongoing crisis that disproportionately impacts Black and Latino residents who live in “food deserts” as a result of segregation and redlining.

Members of the Black Panther Party and Young Lords established free breakfast programs in the 1960s. In the 1990s, former political prisoners and Black Liberation Army activists started the Victory Gardens–Food for Harlem project to unite urban and rural communities, teach former political prisoners to farm, and distribute free food. Food justice work remains a central component of mutual aid organizing across the city; community members set up meal delivery programs, organize food drives, and install free fridges to help feed their neighbors.

.

Housing Justice

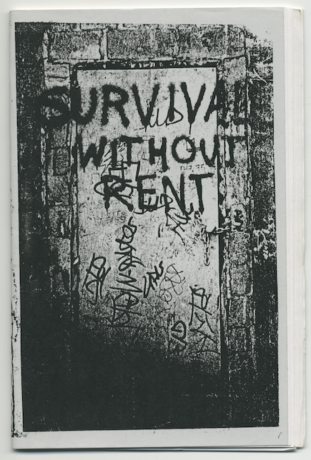

Since the 1960s Black Panther activists and Poor People’s Campaign organizers have insisted on housing as a basic human right–a principle that is at the core of historic and contemporary struggles for housing justice.

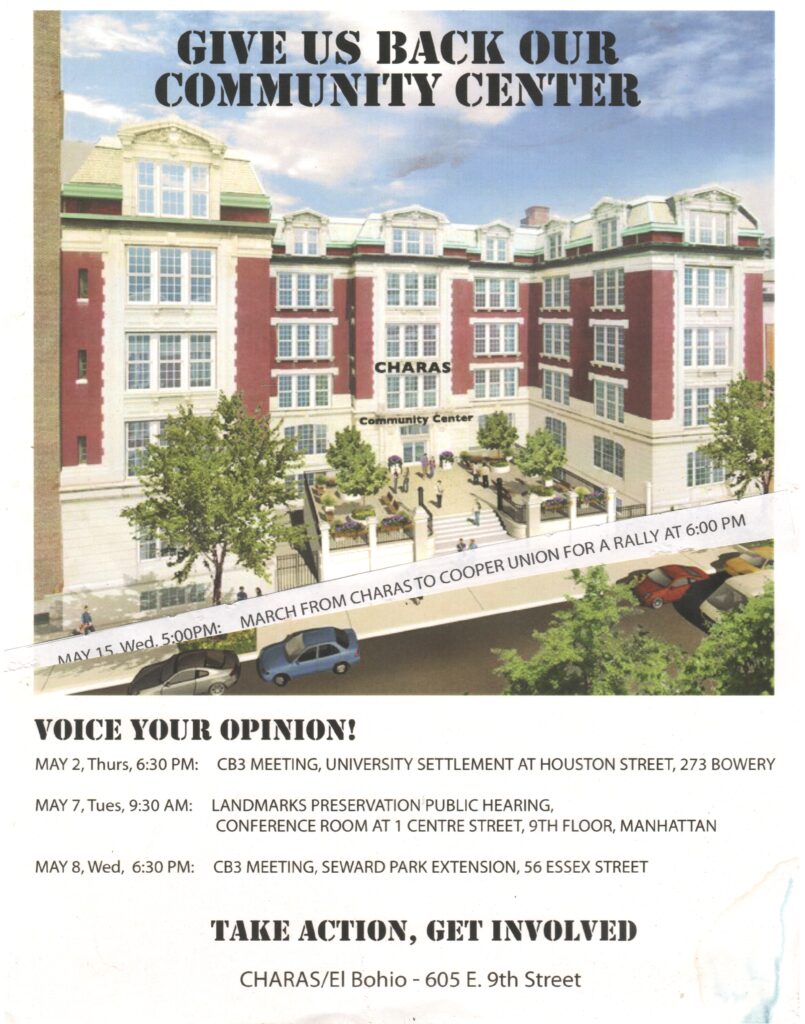

In the late 1960s and ’70s, NYC’s lack of affordable housing spurred homesteading and squatting movements. Residents took control of vacated buildings and rehabbed them with sweat equity. Operation Move-In is an early example: Black and Latinx residents seized vacant buildings in the Upper West Side in the spring of 1970, sustaining almost 200 families through mutual aid projects. Down on the Lower East Side, the East 11th Street movement introduced a model for DIY rehabilitation and cooperative housing that continues to inspire activists today.

The 1980s and ‘90s saw increases in luxury development, rising rents, and militarized aggression against squats and homeless encampments–trends that have only escalated in the years since. In NYC, where the rich fund political candidates who embrace developer-friendly policies, the commons are increasingly privatized, homelessness is criminalized, and we face a continual housing shortage in a city full of empty luxury apartments.

Activists have mobilized in response to rising rents, racist upzonings, and the escalating eviction crisis. Neighborhood coalitions like Families United for Racial and Economic Equality (FUREE) and the Crown Heights Tenants Union have given a voice to residents facing displacement. New Yorkers have organized rent strikes and coordinated legal aid to protect each other with support from long standing organizations like the Met Council on Housing. Grassroots coalitions like the newly formed Brooklyn Eviction Defense (BED) use collective action and mutual aid strategies in the ongoing struggle for housing justice.

.

Street Justice

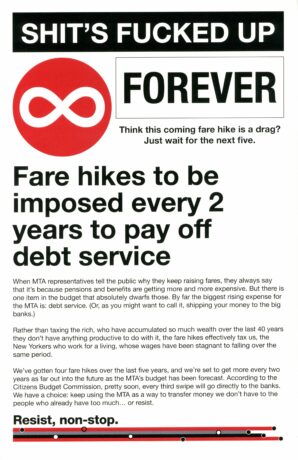

Most New Yorkers don’t own a car—we walk, bike, or take public transit—but drivers dominate our shared streets. The municipal failure to invest in safer infrastructure or better public transportation for New Yokers has fueled creative grassroots advocacy.

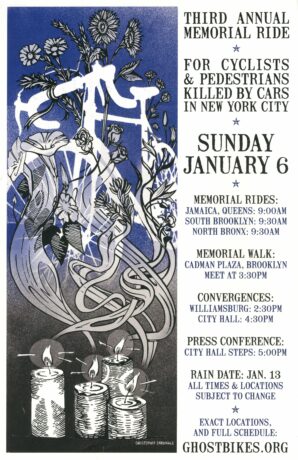

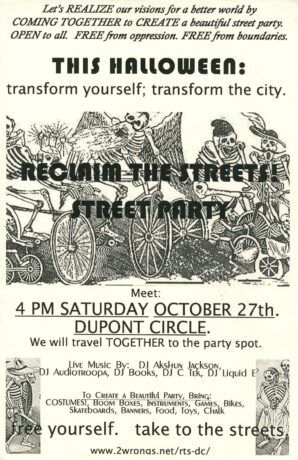

Transportation Alternatives (TA) formed in the 1970s. The group has been a fierce advocate for safer streets for New Yorkers. In the 1990s, Time’s Up! organized monthly Critical Mass rides where hundreds of cyclists took over the streets. Over time, TA and Time’s Up were joined by other groups like Right of Way, Public Space Party, Reclaim the Streets, and Make Brooklyn Safer.

These groups used creative tactics and built collective power; they organized naked bike rides, set up guerilla bike lanes, and established the ghost bike memorial project. The current coalition of traffic justice advocates continue to use civil disobedience and political advocacy to fight for street justice.

Despite progress made by activists, city streets remain contested commons. The negative effects of car-centricity continue to compound. Reckless drivers injure or kill New Yorkers daily. Carbon emissions stay high while congestion pricing plans stagnate. Drivers fight necessary changes, such as bike lanes instead of parking places, despite the threat of climate collapse. The need for safer streets remains urgent.

The Struggle Continues

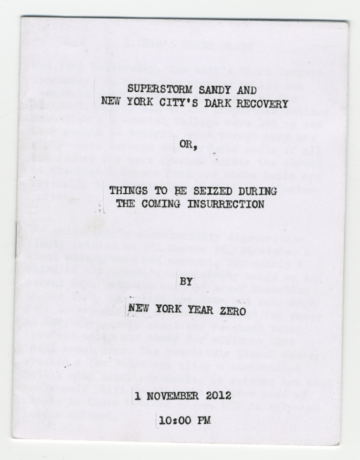

While the political landscape in NYC drifted left in the wake of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, New Yorkers have yet to see meaningful change in land use policies. Instead, we’ve watched politicians co-opt narratives related to equity, housing justice, and environmental resilience to justify massive upzonings in flood prone areas like Gowanus, even as NYCHA residents across the city wait for critical capital repairs.

In Red Hook, home of the the largest NYCHA population in the city, major corporations like Amazon and UPS have installed massive “last-mile” warehouses, bringing fleets of diesel trucks to an area where dozens of brownfields abut major traffic arteries like the Gowanus Expressway. Since 2020, environmental activists and community members have been demonstrating and risking arrest to stop the construction of a massive National Grid fracked gas transmission pipeline in North Brooklyn. The p

Despite setbacks and corruption, New Yorkers continue to agitate and organize. During the pandemic, neighbors came together in a renewed struggle against displacement and gentrification. Some formed tenant unions, mutual aid groups, and eviction watch networks. New coalitions formed to protest the construction of pipelines in North Brooklyn, the destruction of the East River Park, and the criminalization of homelessness in Tompkins Square.

It is easy to forget, in a place like New York where things are constantly changing, that a city doesn’t change itself. It’s our city and these are our streets—so it’s our fight.

This exhibition is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature.

Exhibition Dates

May 21, 2022

September 5, 2022

Opening

May 21, 2022

3:00 PM - 7:00 PM