Hyperallergic: February 6, 2015

Published on April 26, 2024

When Women Fought Nukes with Anarchy and Won

by Daniel Larkin on February 6, 2015

“There is a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other” Madeleine Albright, the first woman to serve as US Secretary of State, once quipped. Albright wanted all women to understand what supporting instead of sabotaging each other could accomplish. In that vein, Brooklyn’s Interference Archive is showcasing a big success story from the 1980s. It’s inspiriting to learn what women activists achieved by forming a web, strengthening one another. “Documents from Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp” was organized by Susan Jahoda and Emma Jahoda-Brown, a mother-daughter team. The exhibition pays tribute to the women who occupied the area surrounding England’s cruise missile installation, reshaping British public opinion and attracting international attention to the nuclear arms race.

Why protest the 96 cruise missiles set in a field 50 miles outside London? For starters, the term “Cruise Missile” deserves ironic quotation marks because it misleadingly understates their capacity. Is “missile” the right word for an atomic warhead with 15 times the payload of the A-bomb that obliterated Hiroshima? Is a nuclear bomb that can travel 1,500 miles to hit its target just on a “cruise”? A roaming robot with the firepower of 15 atomic bombs is what these women found unconscionable.

At least 4,000 “cruise missiles” were globally operational in the 1980s. In 1983 there were enough nuclear weapons to destroy a city the size of San Francisco every half hour for the next 57 years. The world was on the brink, one hasty push of the red button or computer glitch away from nuclear annihilation.

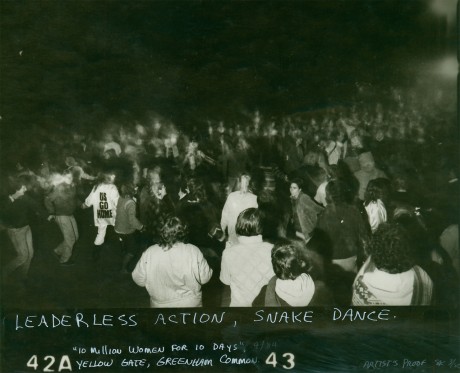

The conventional activist strategies weren’t getting through, so these women got creative and explored how poetic and performative activism just outside the fenced-off missile site could break through the denial. They decorated that fence with pictures, banners, and other objects. They blocked the road to the site with dance performances. They even climbed over the fence to dance in the forbidden zone.

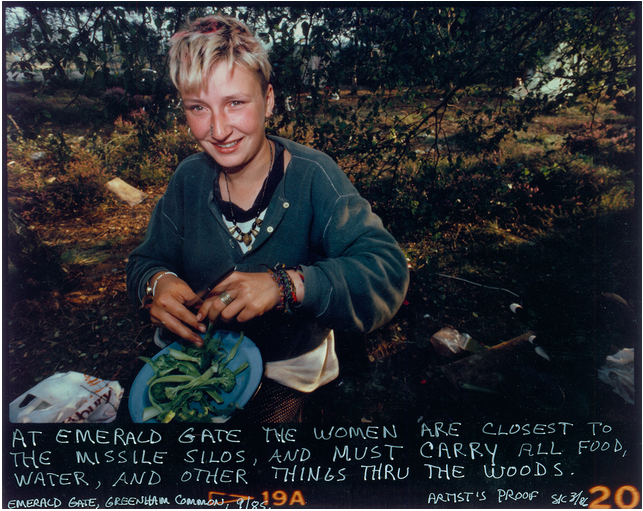

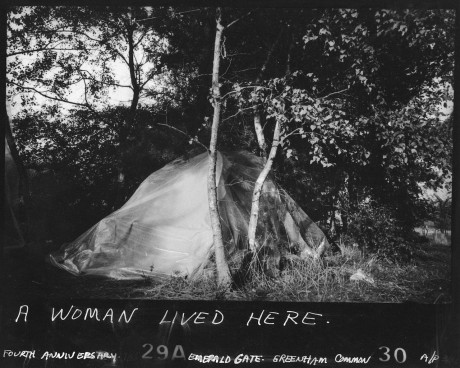

The action began in September 1981, when activists walked 120 miles from South Wales to Greenham Common in Berkshire, southeast of Newbury. What was once a public park had been converted into an airfield to house cruise missiles. At the end of the march, a few women decided to stay and chain themselves to the fence. A camp was formed to enable this protest to continue. More camps came to encircle the base as more women joined the protest. To explain the above map’s legend, each camp was called a “gate” and most were given a color like green or turquoise. For 19 years, until 2000, these activists thwarted police and the elements to take a stand.

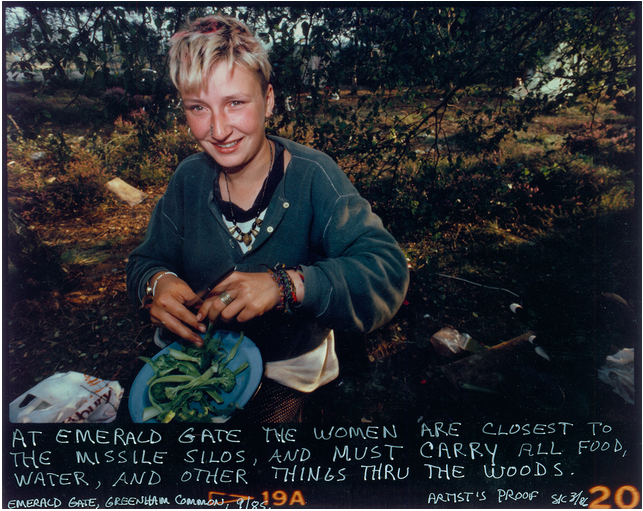

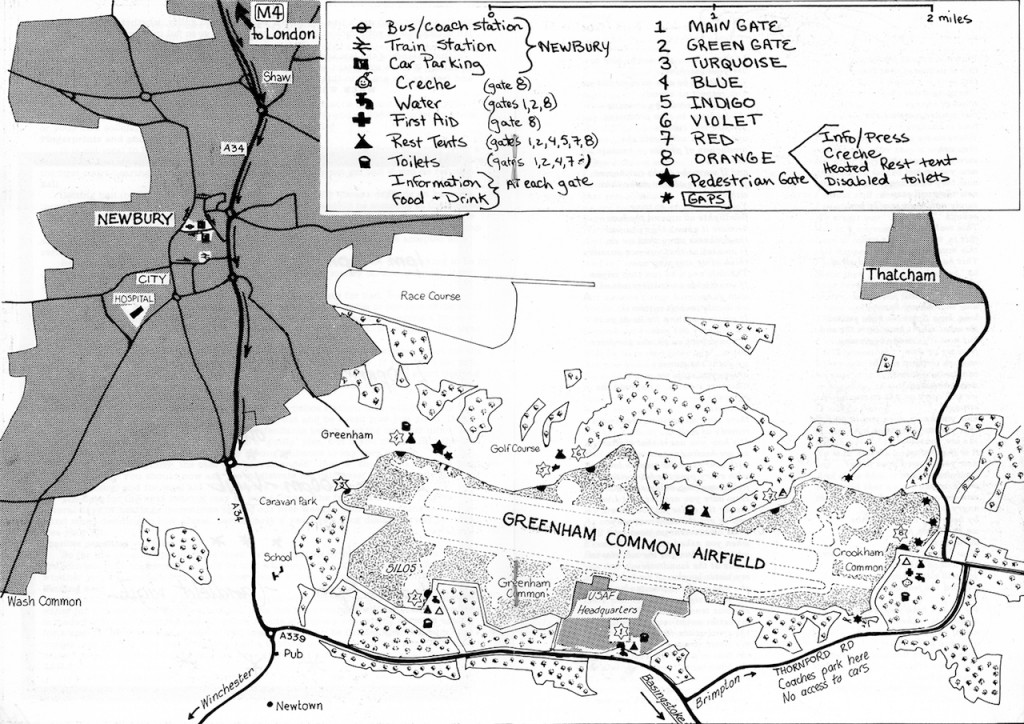

In 1984, the interdisciplinary American artist Susan Kleckner came to document the Greenham camps. She returned twice more in the mid-1980s. Her photographs and their captions open a window into the daily lives of these women. Kleckner’s work forms the visual core of the exhibition, which supporting documents and photos contextualize.

Kleckner’s photographs don’t have conventional titles, but the captions help you to unpack the image. For example, “Untitled (Many Women Believe Anarchy Works…)” (1984) demonstrates how the camp was sustained by anarchist principles. Many women thought it worked best to engage in collectivist decision-making. And so did the many people who donated food so the women could survive the winter.

Images of women dancing in leaderless actions and reaping in food donations can create a misleading “kumbaya” impression. In fact, there were bitter arguments in the camps. The women disagreed about whether to speak kindly or harshly to the base’s guards, whether it was ethical to cut the fence during trespassing interventions, how to interpret the principle of non-violence, and perhaps the most vexing question of all — the role of men at the camp. But the women all agreed that nuclear arms were unsustainable and that a heterogeneous web of leaderless women could change hearts and minds.

The geography of the site enabled the women to defuse ideological differences organically, by separating into the different camps that surrounded the site. It enabled the women to live in a manner that each clan found ideologically and practically suitable. But the arrangement also allowed them to come together for conversations, actions, and to provide logistical support to one another.

It is difficult to address the activists’ decision to exclude men from living at the camps without lapsing into the tired clichés contrasting men and women. A documentary by Jahoda-Brown, which plays in the exhibition and is available online, allows the women at the camp to speak for themselves and explain the empowering significance of having maintained a women-only camp.

How does one measure the success of an activist camp? In 1991, after a decade of occupation, cruise missiles were removed from Greenham Common. It would be unfair to underestimate the role of the women’s activism. Just as the short-lived Occupy Wall Street camp at Zuccotti Park popularized the idea of the “one percent” to clearly articulate income inequality, the camp was widely discussed in the press, in activist circles, and acknowledged in public statements by Margaret Thatcher and other politicians. We will never know how deeply it penetrated politicians thoughts, but a change of heart took place.

Lao-Tzu once wrote that the “Soft overcomes the hard; the gentle overcomes the rigid. Everyone knows this is true, but few can put it into practice.” Greenham Commons exemplifies one of those moments when non-violence was put into practice and won through dogged patience. This exhibition offers lessons and inspiration for the next generation of activists seeking to overcome the hard with the soft, the rigid with the gentle, and violence with peace.

Documents from Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp will be on view at the Interference Archive (131 8th Street, Suite #4, Gowanus, Brooklyn) through March 1st. There will be an open house event during which visitors can meet and converse with women who camped at Greenham on Saturday, February 7, 2–6pm. The documentary Living Along the Fenceline, will be screened on Friday, February 6 at 7:30pm.

Originally posted at Hyperallergic.com