Exhibition Dates

March 26, 2015

June 15, 2015

New York City is a city of tenants; close to seventy percent of the city’s residents occupy over two million apartments. Rent regulation, including rent control and rent stabilization, covers over a million of these units. That number is dropping daily, due to the gradual weakening of the rent regulation system; predatory equity, which favors the acquisition of capital over the housing rights of long-term residents; and the daily actions of abusive landlords who harass and evict tenants. However, for the past century, New Yorkers have continuously organized to claim the right to live in a city that is integrated and affordable.

This rich history of tenant struggle includes neighborhood resistance to urban renewal in the South Bronx, integration struggles at Stuyvesant Town and in Brooklyn, rent strikes in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant, the coordinated takeover of vacant housing during Operation Move-In, and repeated campaigns to renew and strengthen the rent laws.

This exhibition highlights the diverse array of tactics employed by tenant organizers, and situates the fight for affordable housing within racial and economic justice struggles.

This exhibition was developed in collaboration with:

- Asian Americans for Equality

- Banana Kelly CIA

- CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities

- Community Action for Safe Apartments (CASA)

- Cooper Square Committee

- Crown Heights Tenant Union

- Equality for Flatbush

- Flatbush Tenant Coalition

- Metropolitan Council on Housing

- Southside United HDFC – Los Sures

- St Nick’s Alliance

- Tenants and Neighbors

- United Community Centers

- Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB)

This exhibition was organized by Maggie Schreiner with Ash Bayer, Bonnie Gordon, Lani Hanna, Jen Hoyer, Karen Hwang, and Greg Mihalko. Details about the original physical exhibition, as well as related programming, are available here.

Contents

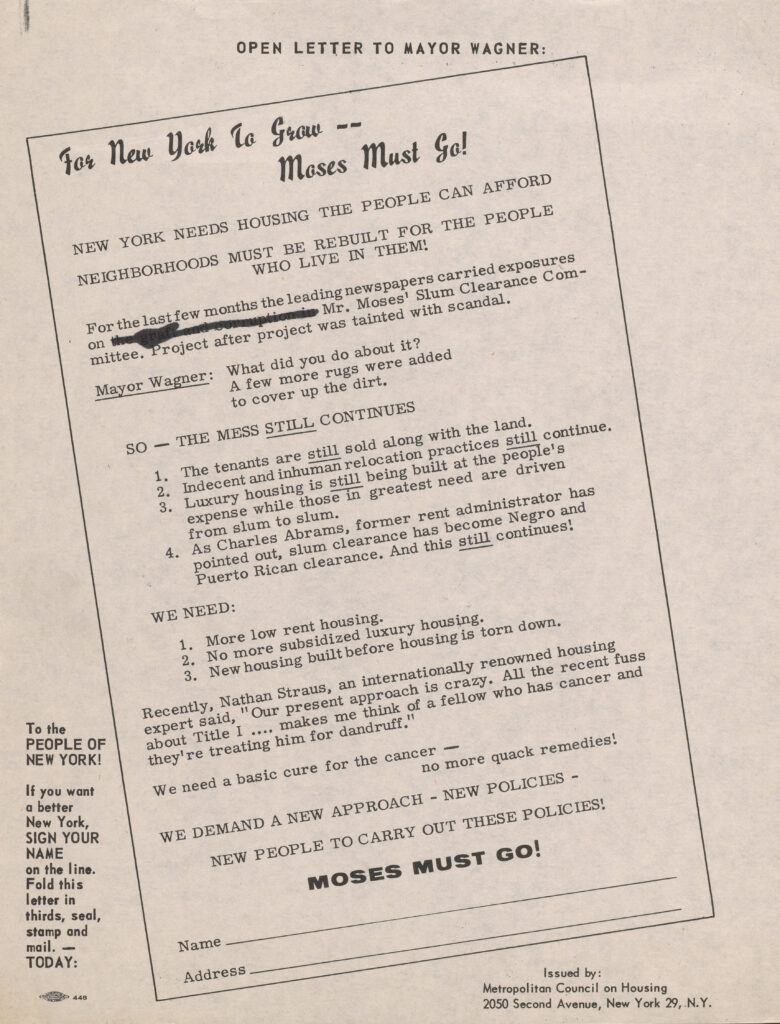

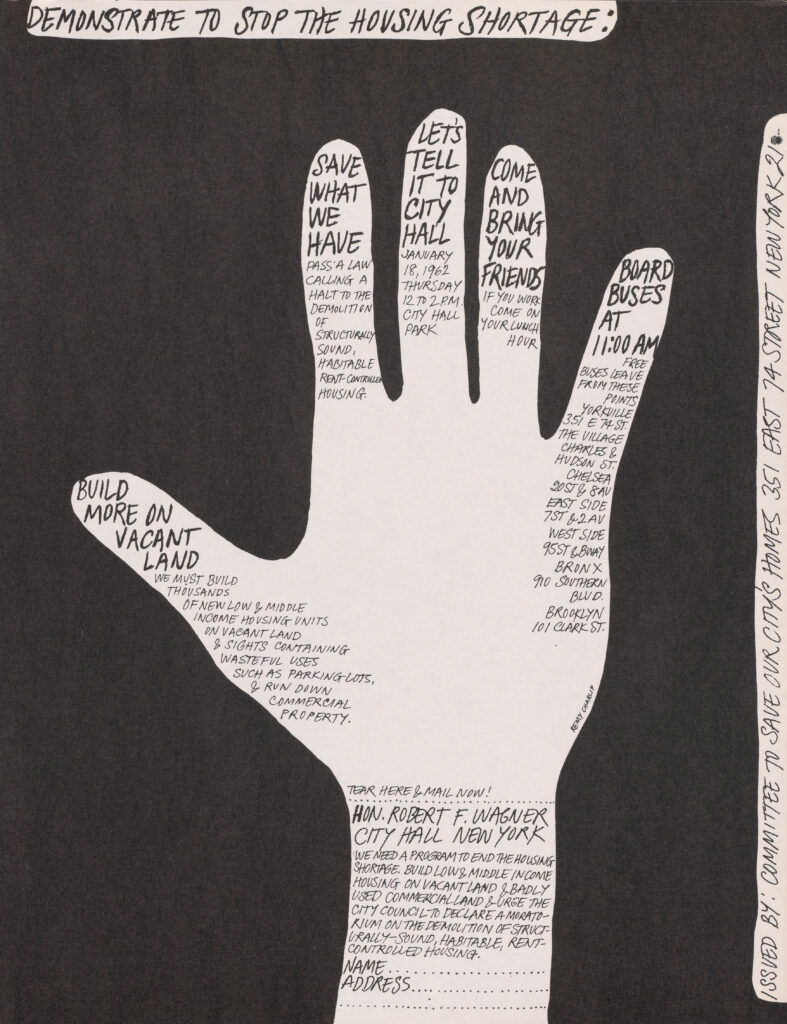

Urban Renewal

Urban renewal, made possible by Title I of the 1949 Federal Housing Act, involved the widespread demolition of working-class neighborhoods in favor of middle-class housing developments. By 1959, sixteen massive projects had displaced over 100,000 people, who were disproportionately people of color. Across New York City, urban renewal projects led to mass relocations and increased residential segregation.

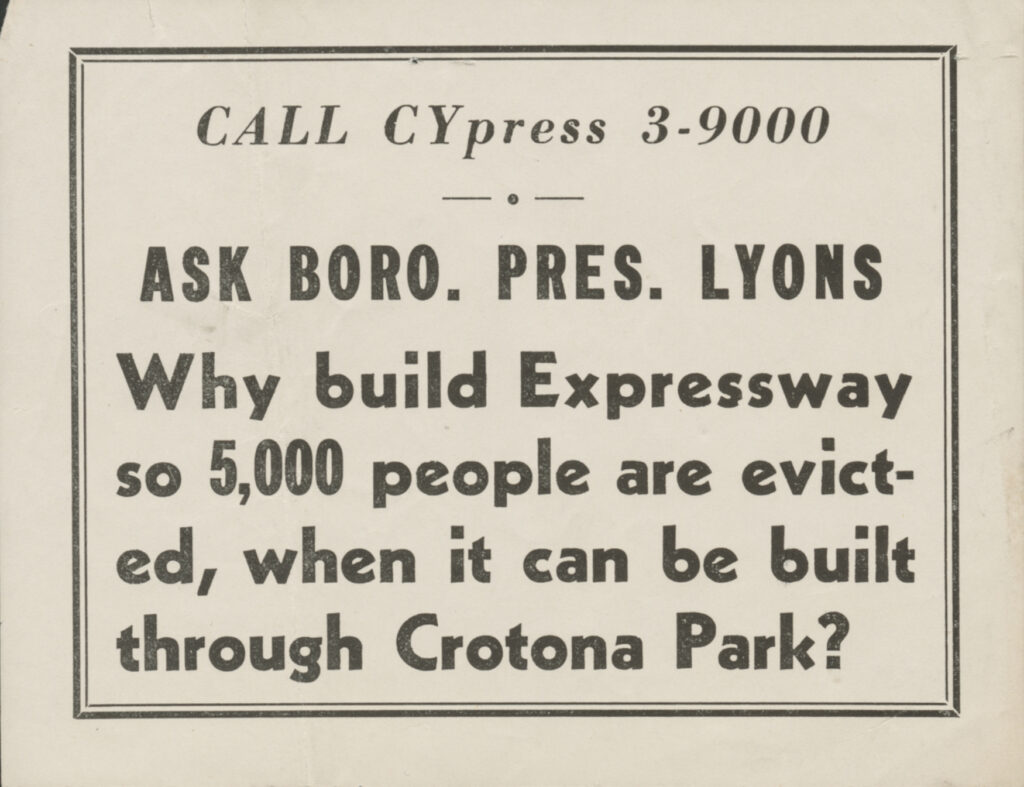

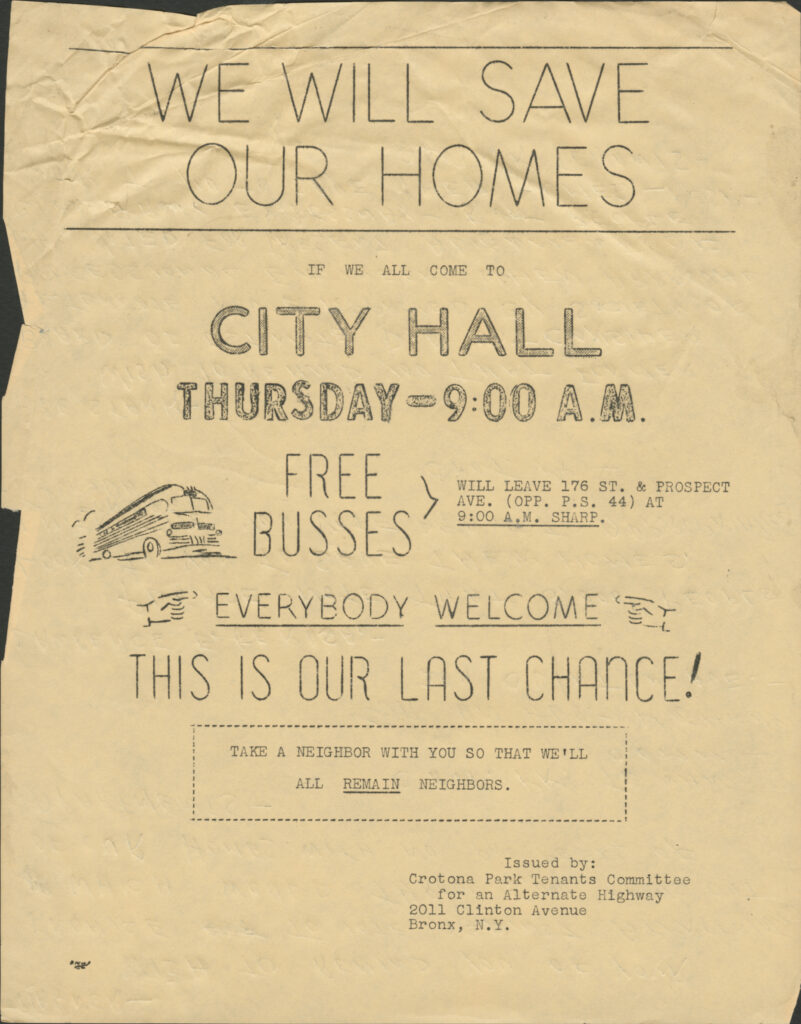

On December 4, 1952, over 1,500 families in East Tremont were served eviction notices in advance of the construction of a one-mile segment of the Cross-Bronx Expressway. Although the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway was not funded through the Title I program, it involved many of the same features. Residents of the densely populated and tight-knit neighborhood formed the Crotona Park Tenants Committee to fight the highway plan. The committee testified and lobbied elected officials, as well as conducting a feasibility study of an alternate route. Planning czar Robert Moses intimidated local officials into supporting his plan, which ultimately caused the displacement of over 5000 people.

Integration

Stuyvesant Town

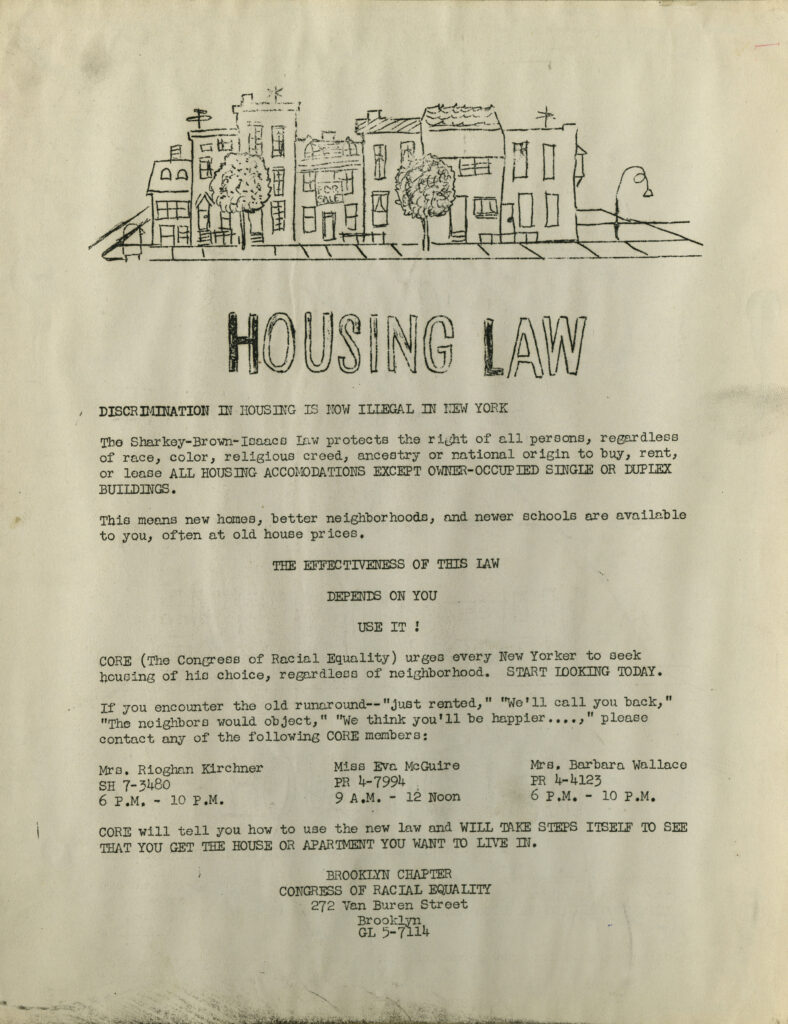

In the midst of WWII, the City of New York and the MetLife Insurance Company announced an urban redevelopment project for returning veterans. The publicly subsidized, private, and for-profit development would have a whites-only policy. When the project opened, new residents formed the Town and Village Tenants Committee to End Discrimination in Stuyvesant Town and began to sublet to African-American families. Public pressure and outrage led to the passage of the Brown-Isaacs law, which banned discrimination in publicly subsidized private housing. After attempting to evict the leaders of the tenants’ committee, MetLife began reluctantly to comply with the new legislation.

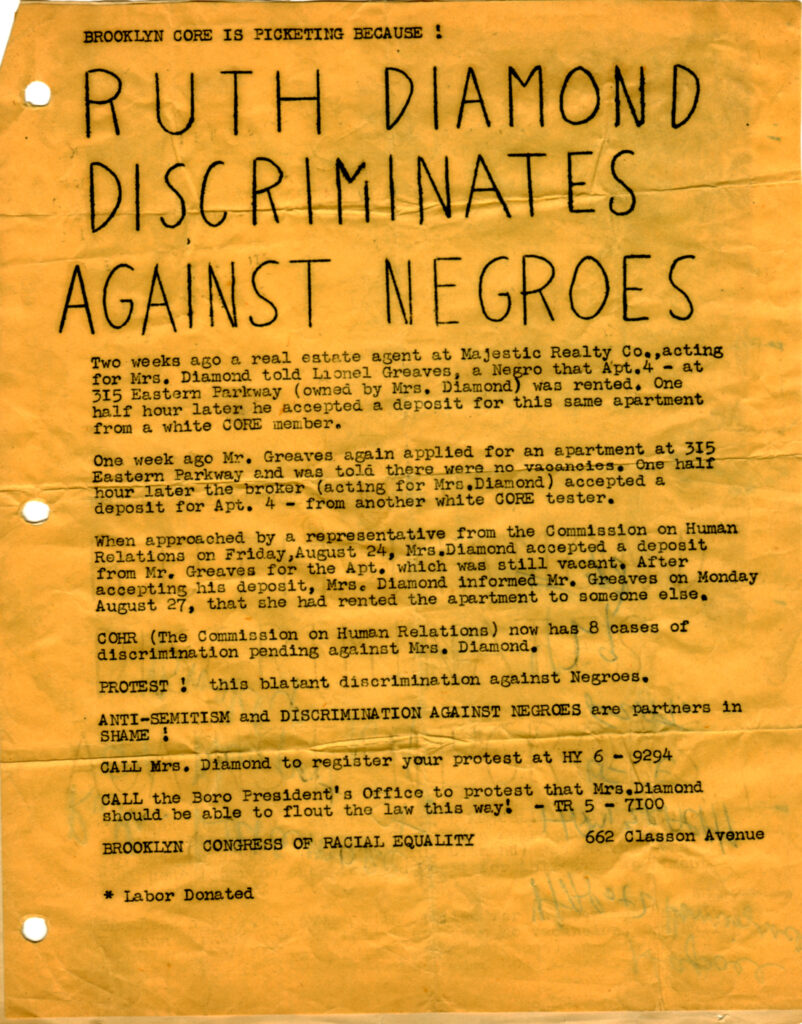

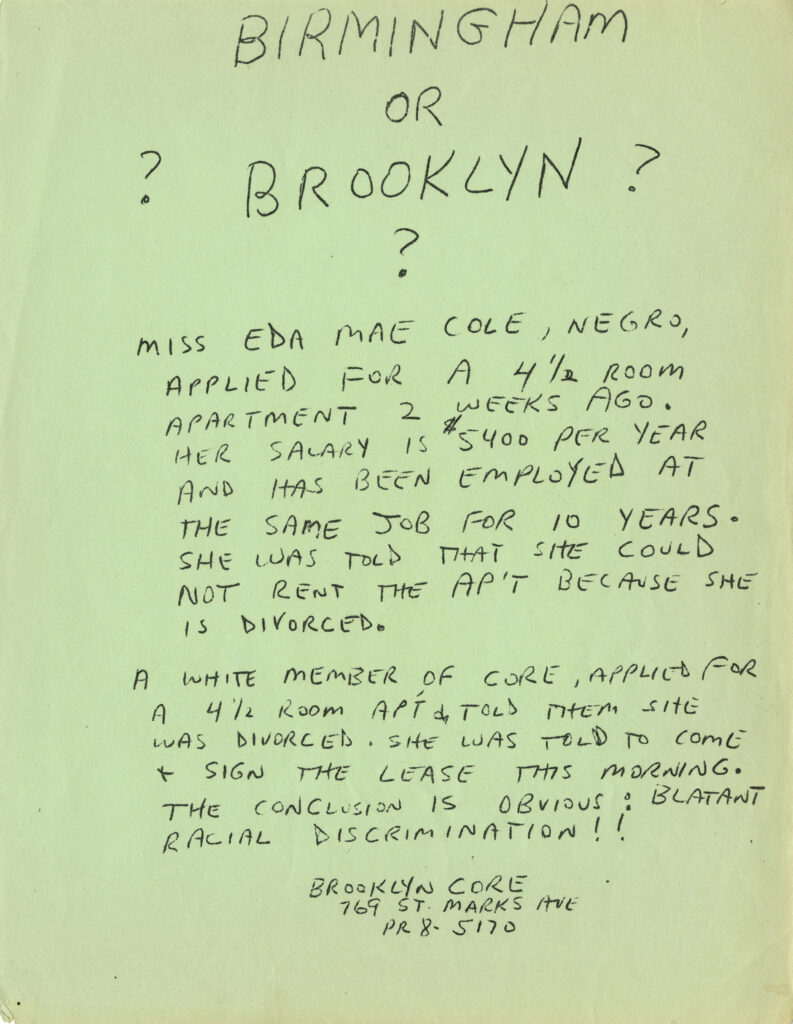

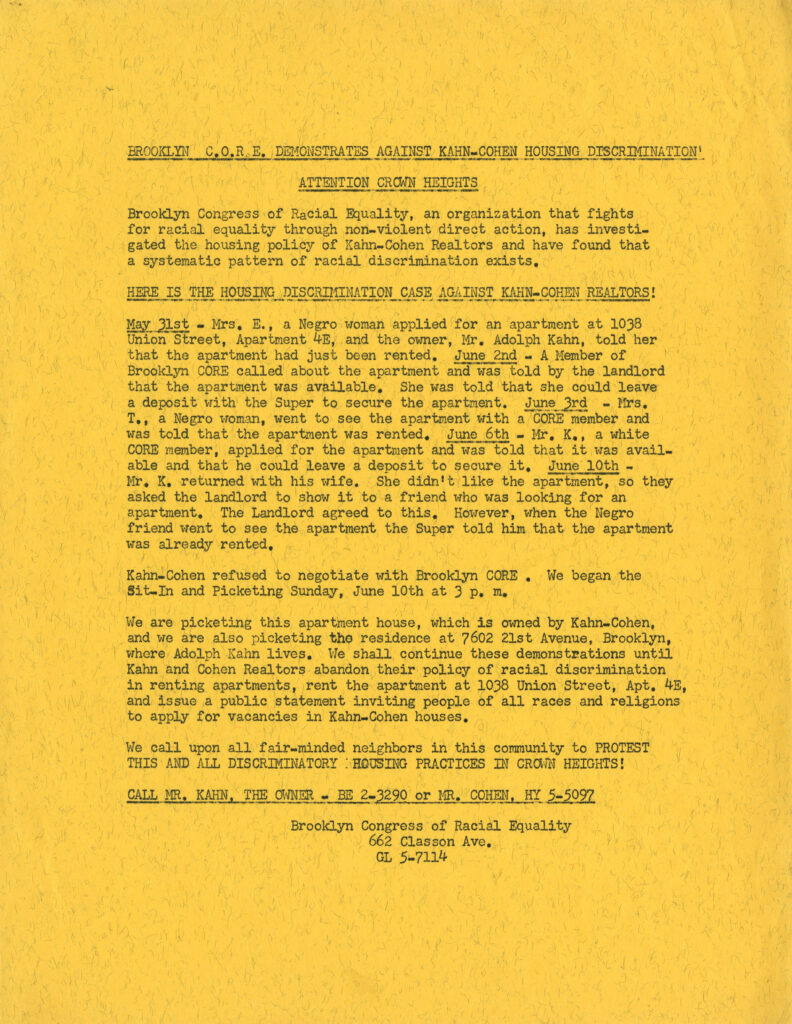

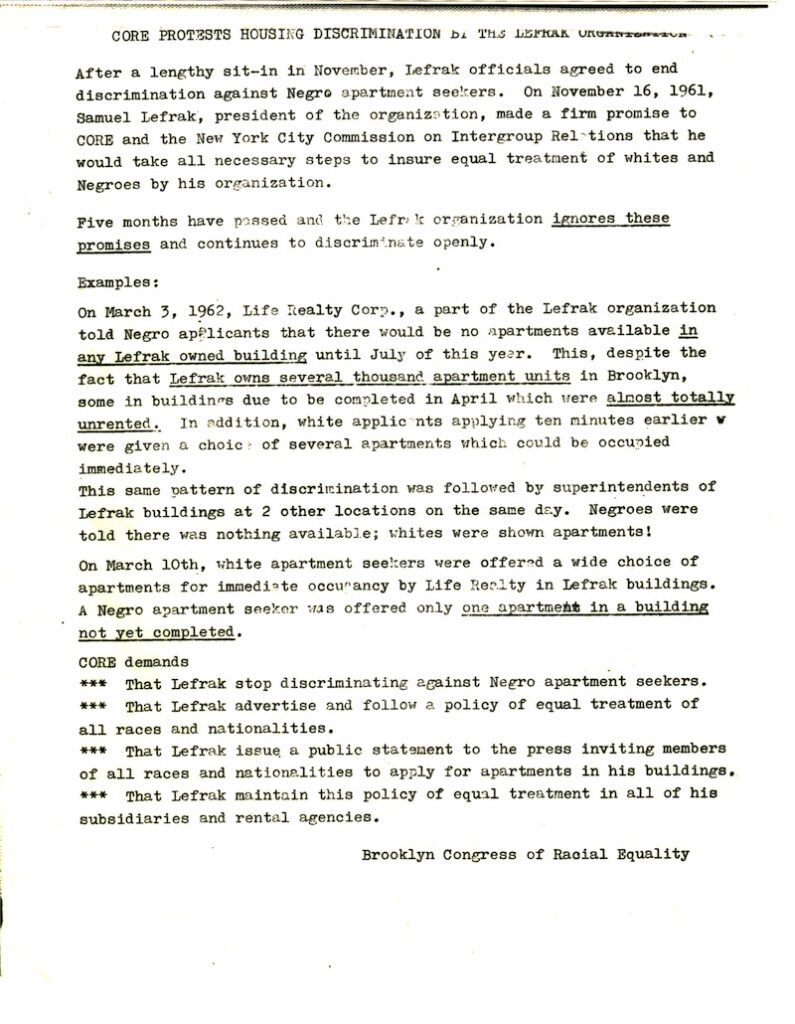

Brooklyn Congress of Racial Equality

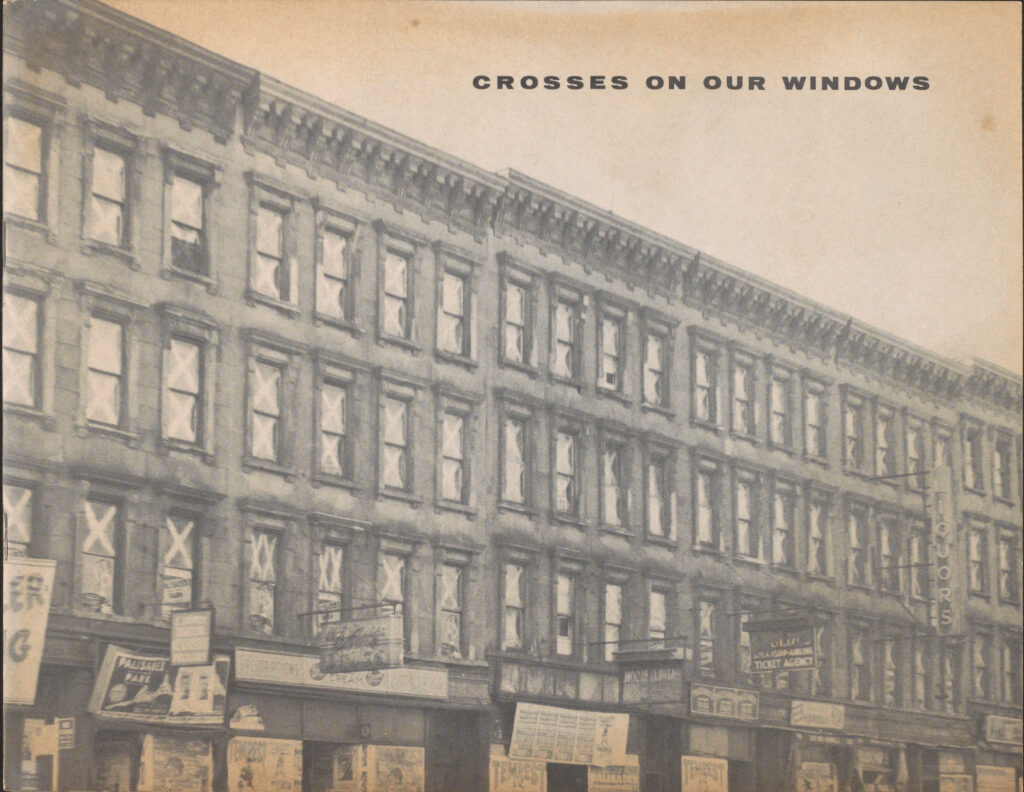

In the mid-20th century, structural discriminations, such as urban renewal and redlining, intensified long-standing housing segregation throughout NYC. By the 1960s, outright discrimination in housing was legally prohibited, so homeowners and realtors would quietly discriminate by telling black apartment searchers that the advertised apartments were no longer available. The Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) conducted direct actions to combat these practices. When black applicants were denied apartments, Brooklyn CORE would send white “testers” to apply for the same apartment, and would document the pattern of discrimination. CORE members would then threaten to report the realtors to government agencies, or hold pickets, sit-ins, and sleep-ins to publicize the discrimination.

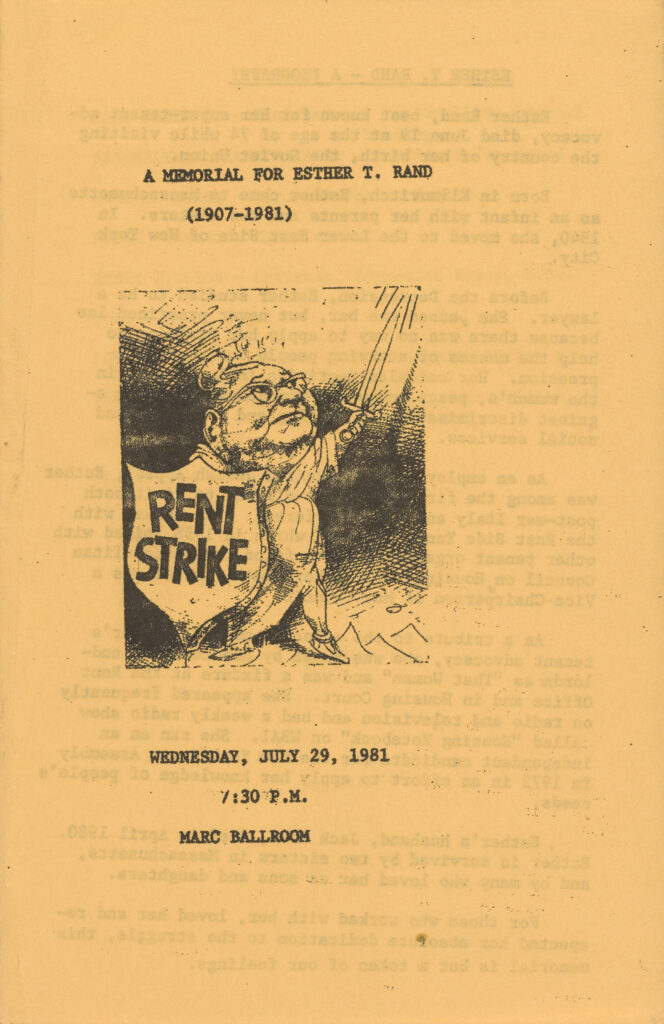

Rent Strikes

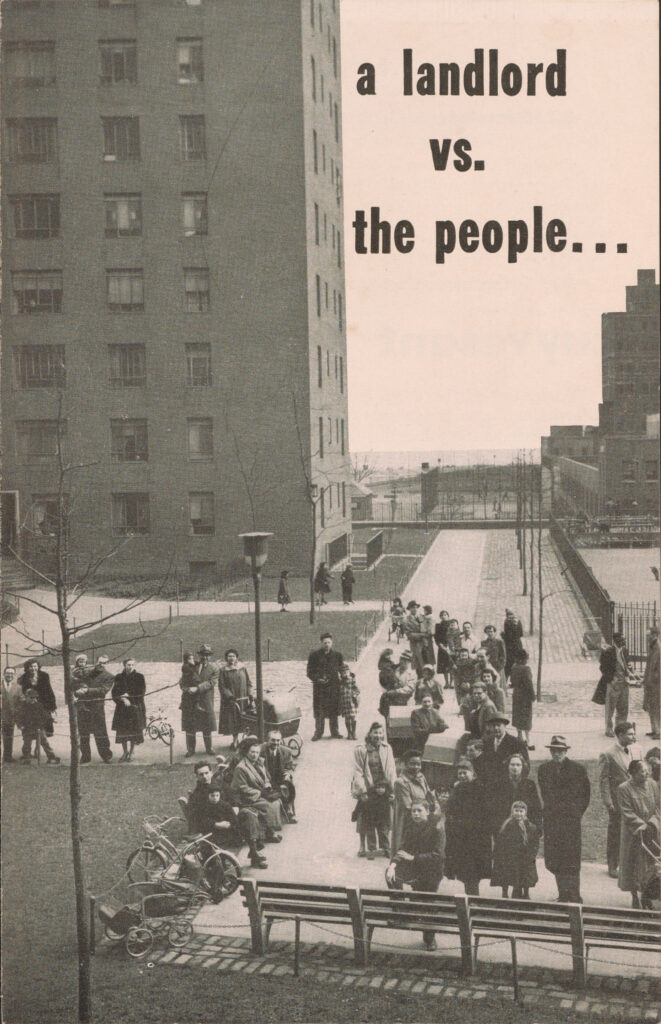

A rent strike is a tactic in which a group of tenants come together and collectively agree to refuse to pay their rent until the landlord meets a specific list of demands. In the 1960s, rent strikes were often adopted as a tactic in response to widespread landlord negligence due to low vacancy rates caused by urban renewal and segregation.

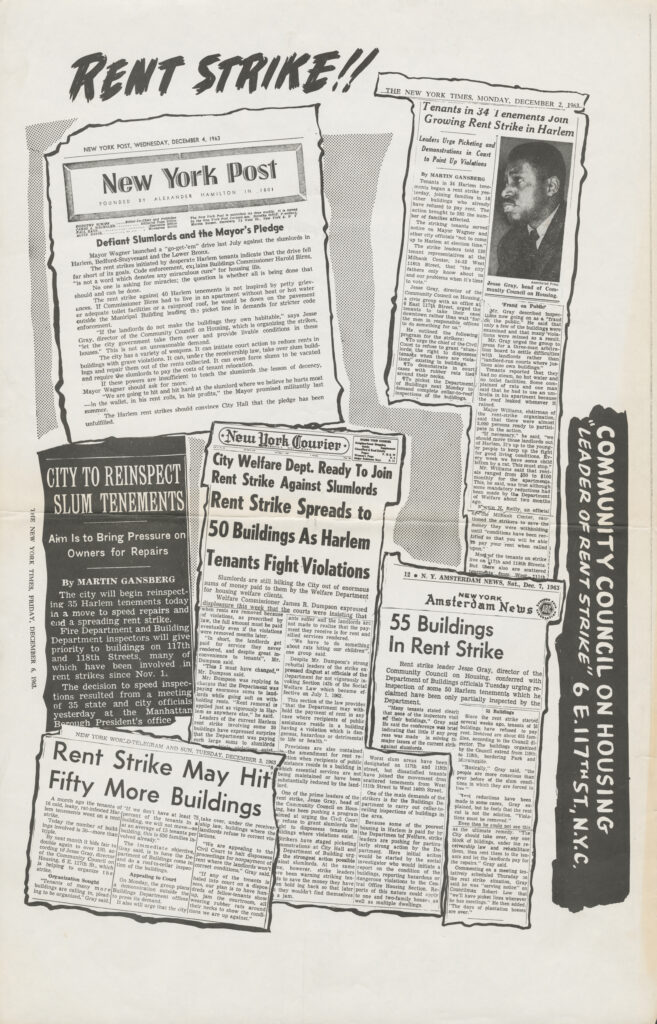

Harlem

In 1963, Harlem tenants initiated a large rent strike as the culmination of more than a decade of organizing efforts by the Community Council on Housing and activist Jesse Gray. When tenants appeared in housing court, they presented the judge with dead rats to dramatize their living conditions. The judge legalized the rent strike, allowing tenants to pay money to the courts instead of their negligent landlords. However, the poor conditions in the apartments were rarely ameliorated.

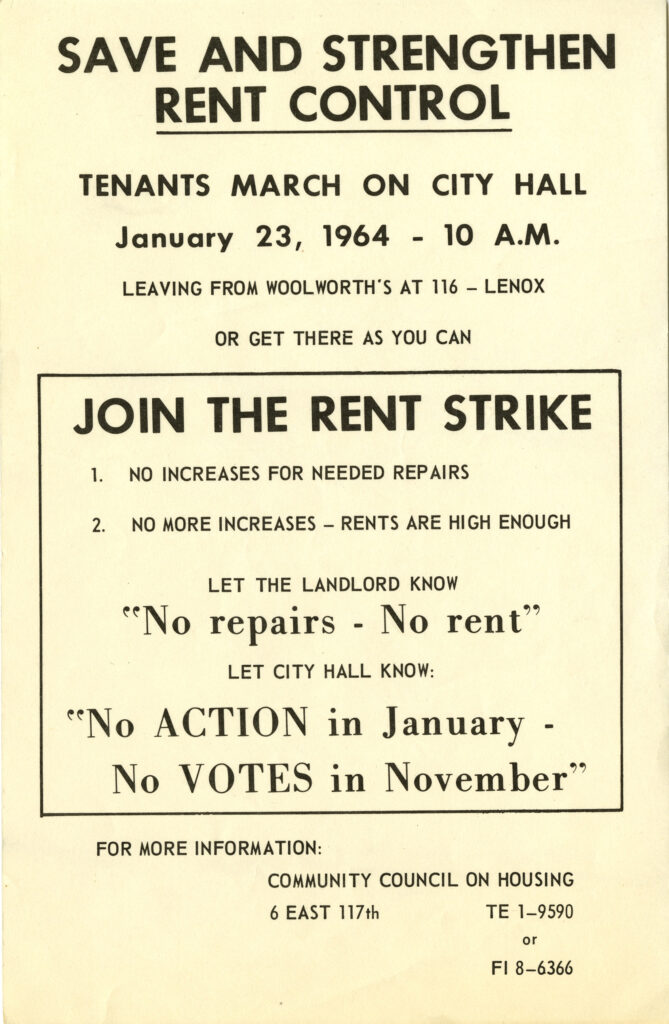

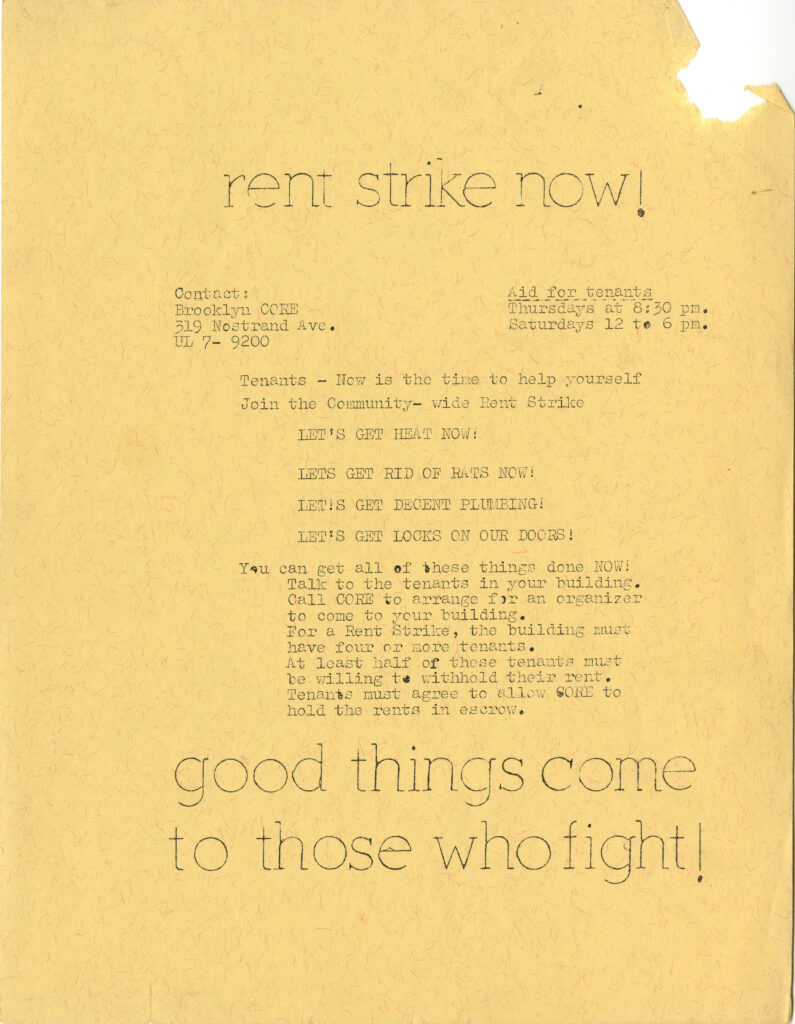

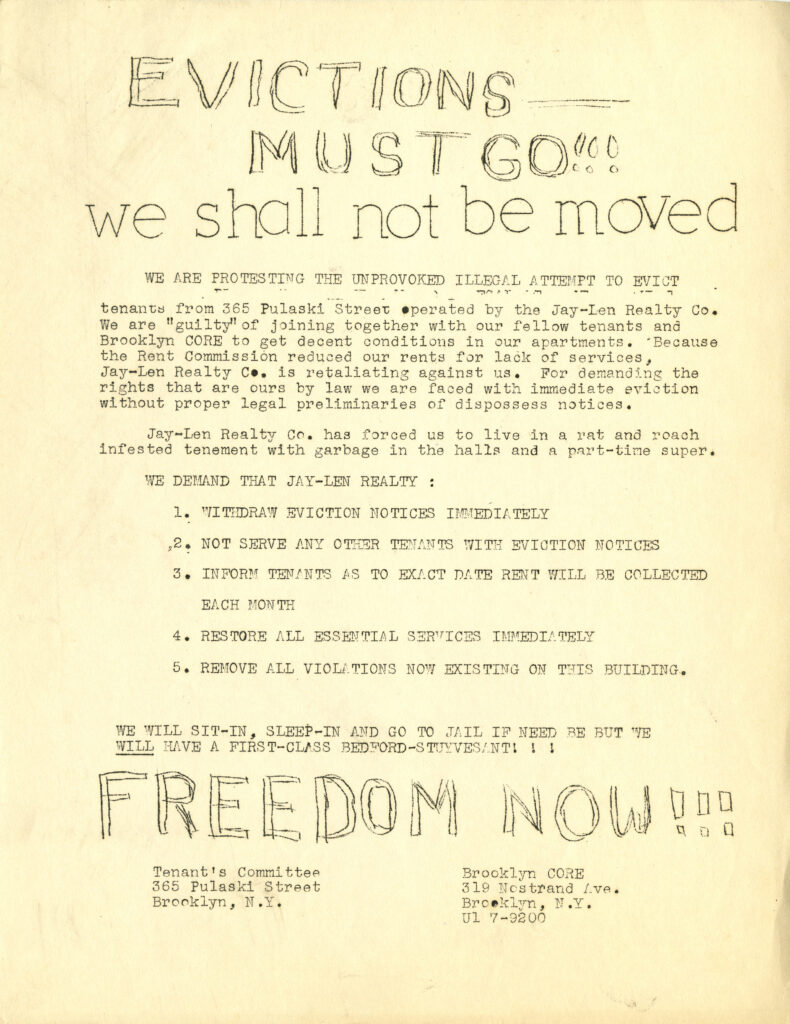

Bedford-Stuyvesant

National civil rights actions during 1963 and 1964 transformed the Harlem rent strike into a larger social movement, and the tactic quickly spread across the city. Brooklyn CORE formed a Rent Strike Committee in August 1963 and led four buildings in Bedford-Stuyvesant and one in Brownsville in a rent strike campaign. Organizers and tenants picketed landlords’ homes, petitioned city agencies, and conducted tenant education sessions.

“The major aim of the rent strike committee is to teach people to fight for themselves. On the specific problem of living conditions and, in the future, on civil rights problems concerning the human condition, we expect each building organized by CORE to serve as a fighting unit. The people will never again become victims if they themselves lead the fight.”

– Brooklyn CORE organizer, Major Owens (later a 12-term Congressman)

Establishing Rent Control and Stabilization

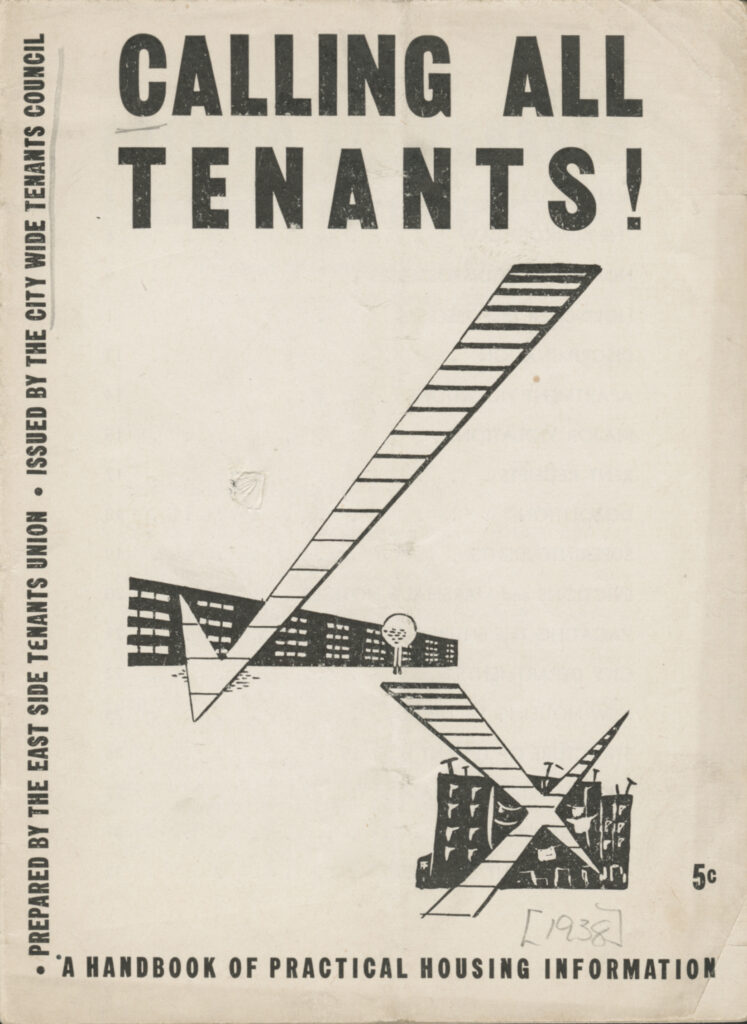

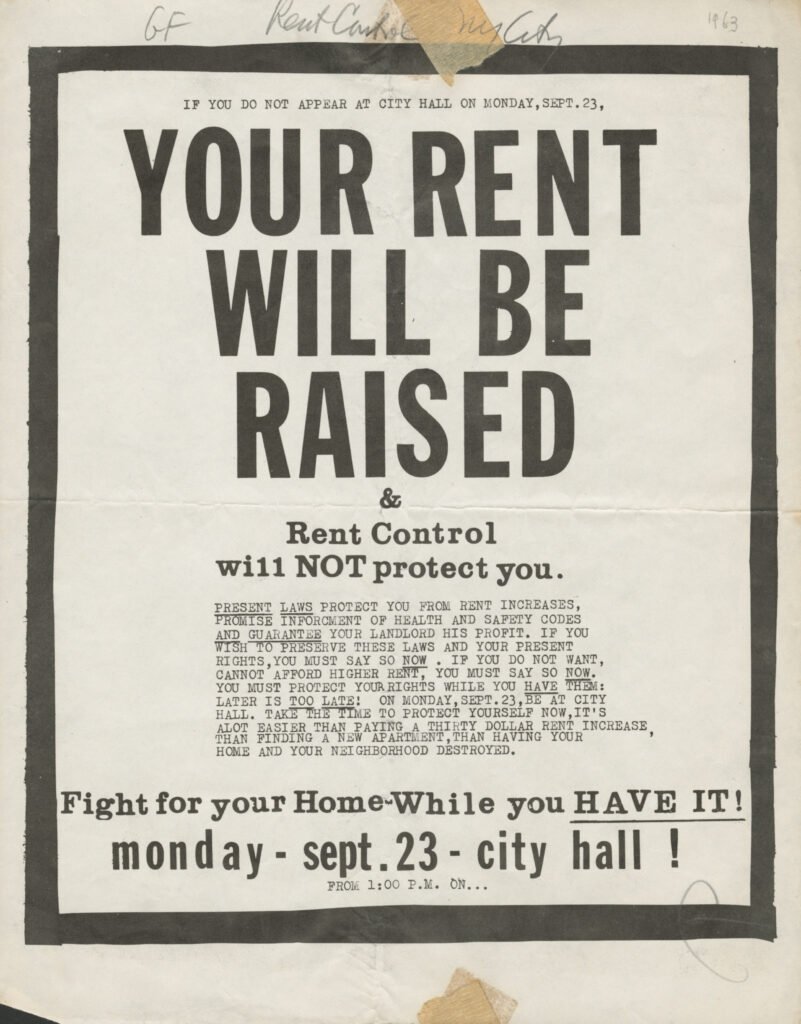

Fighting for Rent Control

In 1943 the federal government imposed a NYC rent freeze through the wartime Office of Price Administration. After the end of WWII, tenant organizers fought successfully to have these federal controls replaced with New York State rent control, and eventually New York City rent control. In 1969, a weaker regulatory system called rent stabilization was enacted. The Rent Guidelines Board was created to determine annual rent increases for rent-stabilized apartments.

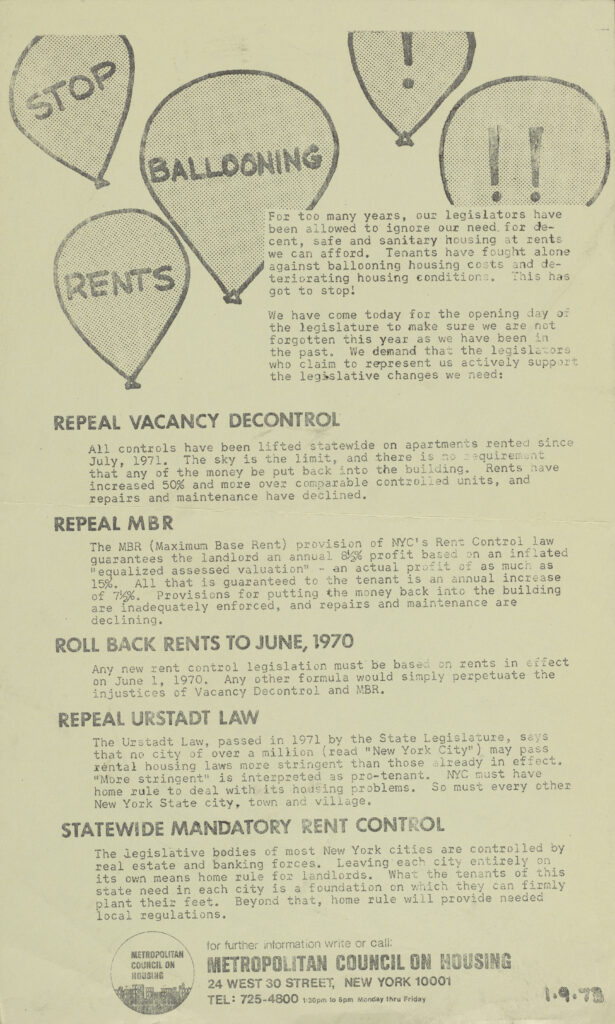

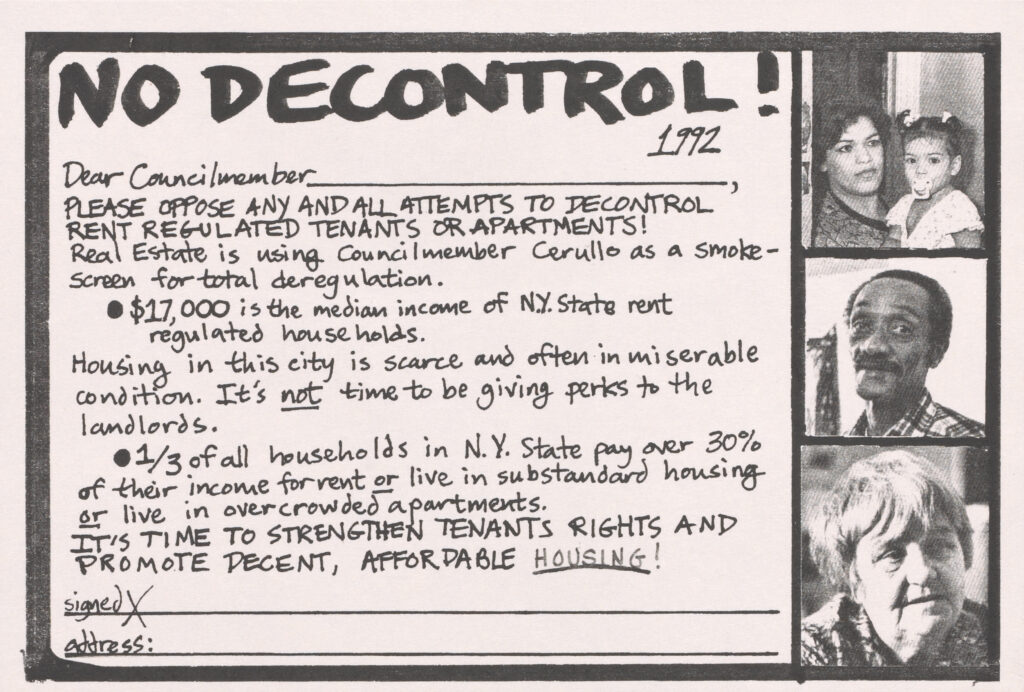

Neoliberalism and the Dismantling of Rent Control

New York City during the 1970s was overshadowed by recession and conservative backlash. At the beginning of the decade, the real estate and landlord lobby, paired with the neoliberal policies of Governor Nelson Rockefeller, attempted to destroy the rent control system. A package of six “decontrol” bills moved rent regulation from municipal to state jurisdiction, and introduced “vacancy decontrol,” which withdrew apartments from the rent regulation system whenever they were vacated. These laws rapidly resulted in a huge increase in evictions.

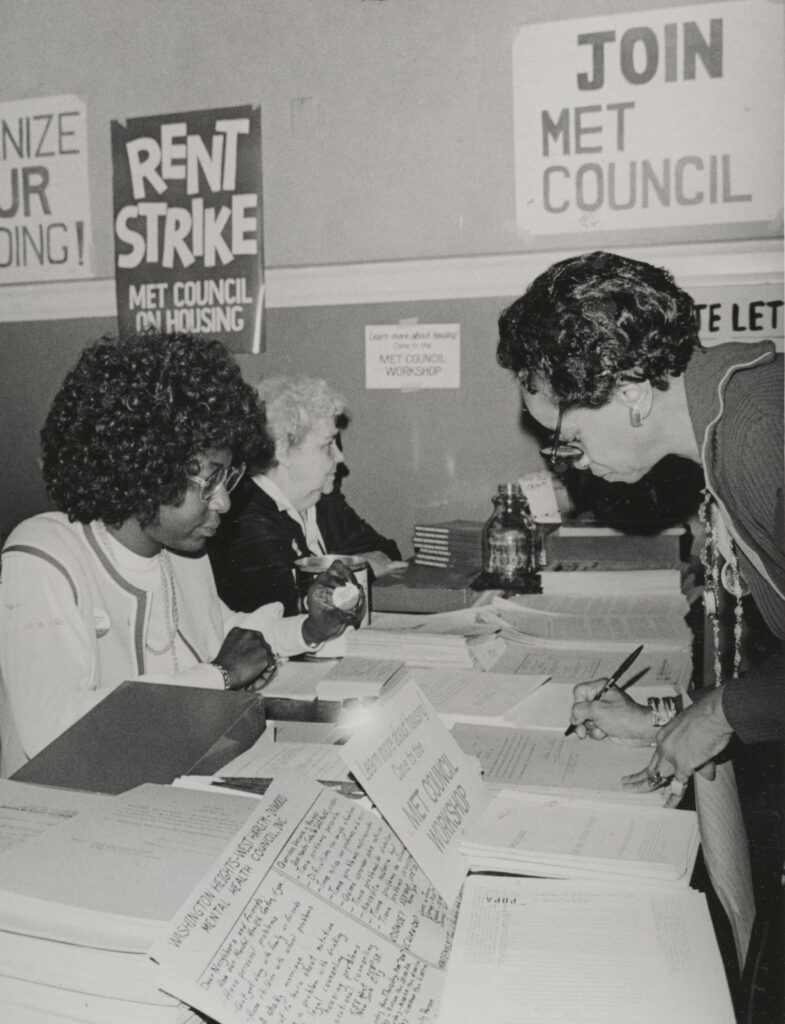

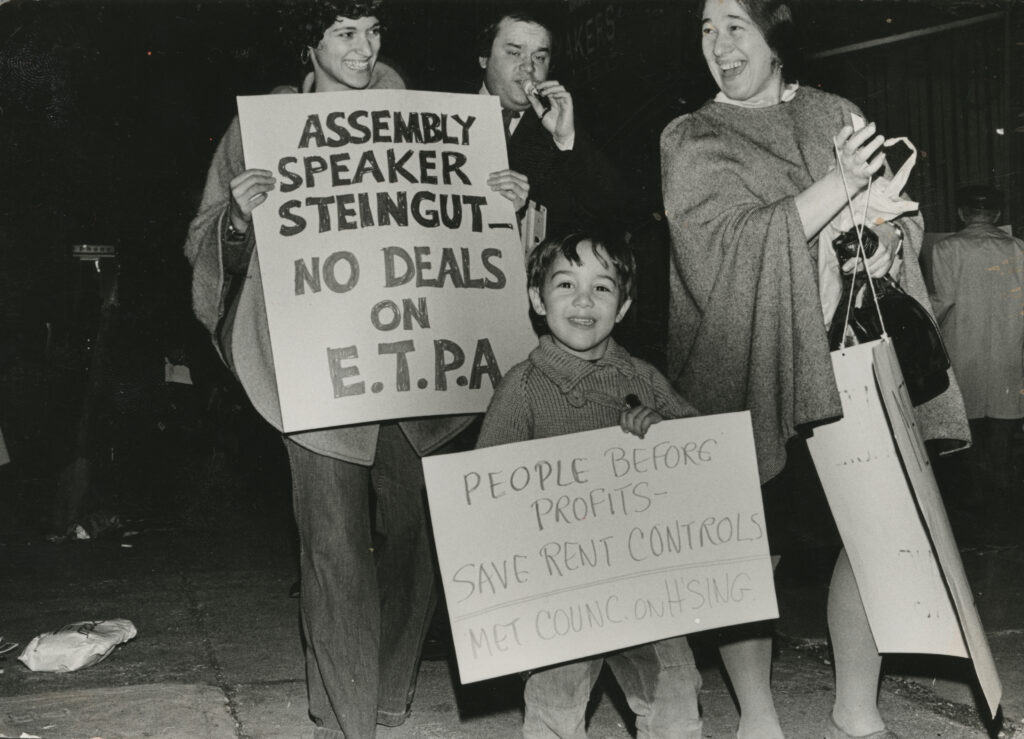

Tenants responded to these major setbacks with extensive organizing. In 1974 the Emergency Tenant Protection Act (ETPA) was passed, which extended rent stabilization to most of the older apartments that had been affected by vacancy decontrol.

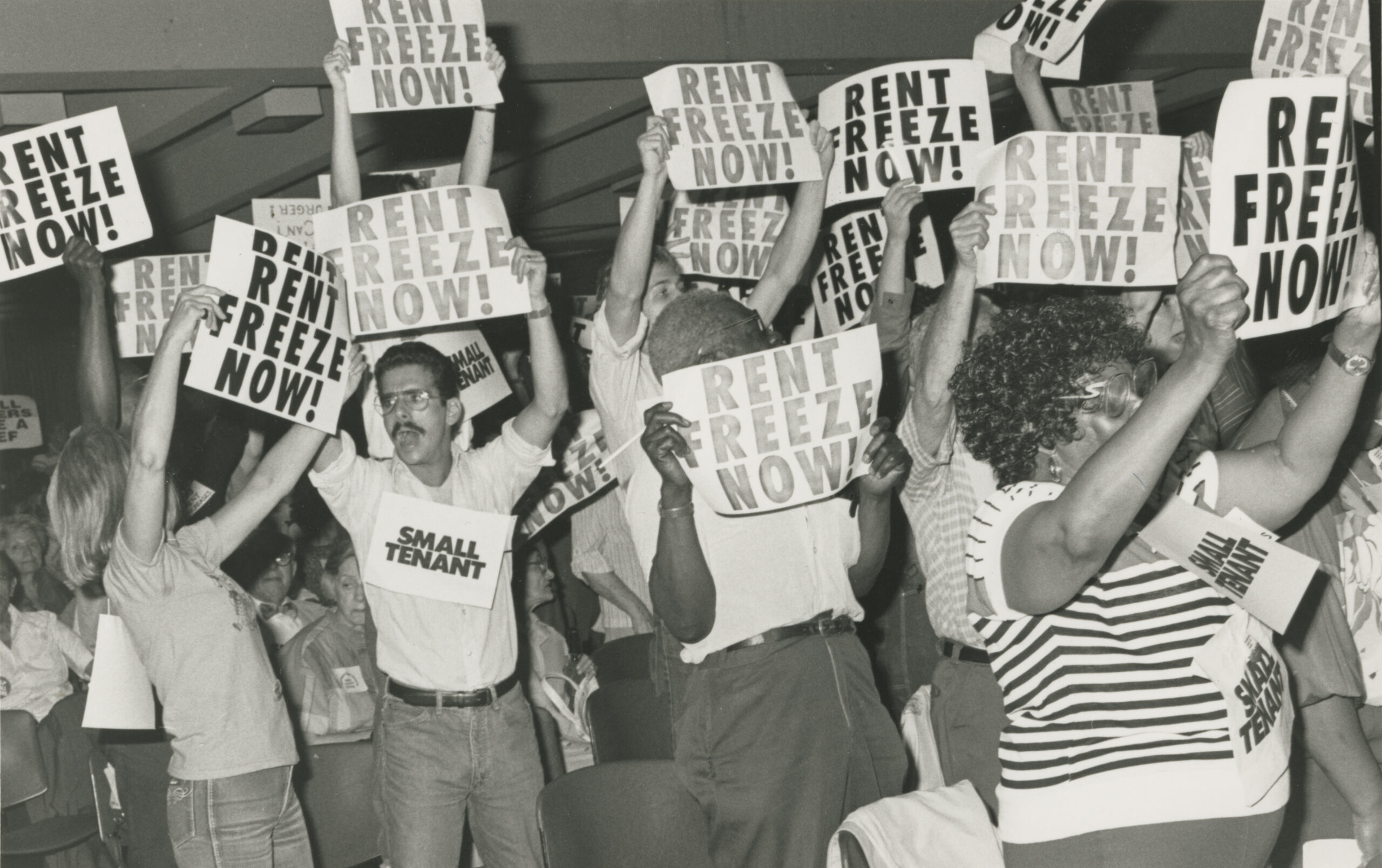

(1974). Photograph by Bea Oakley,private collection of the Metropolitan Council on Housing.

Vacant Housing

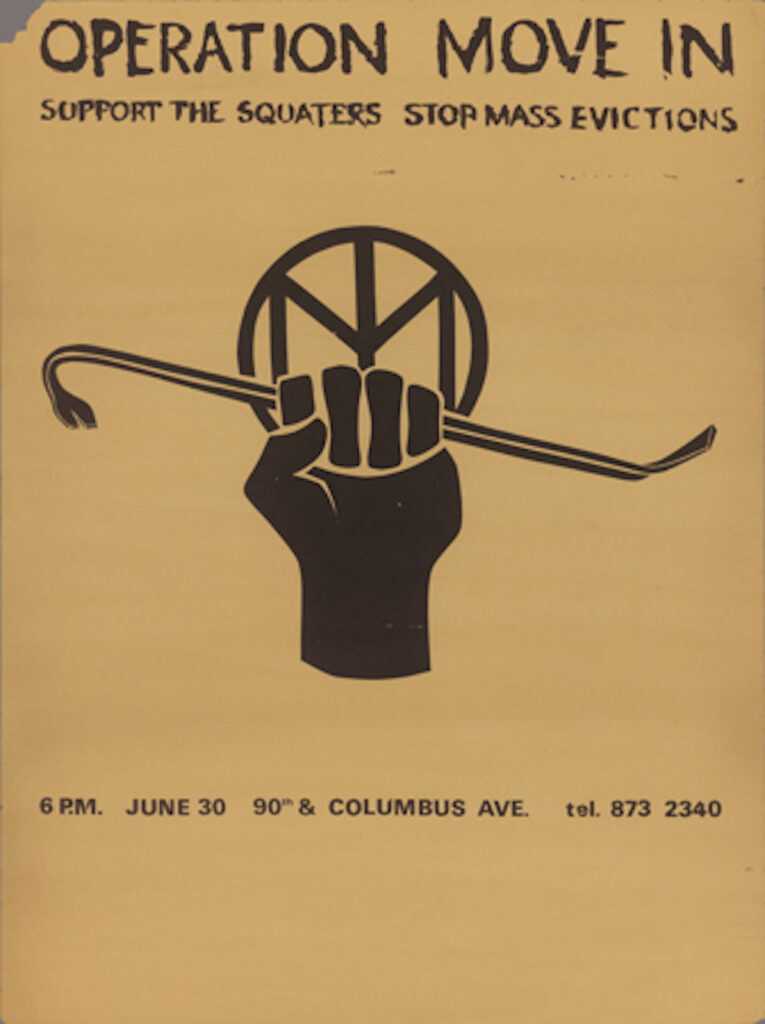

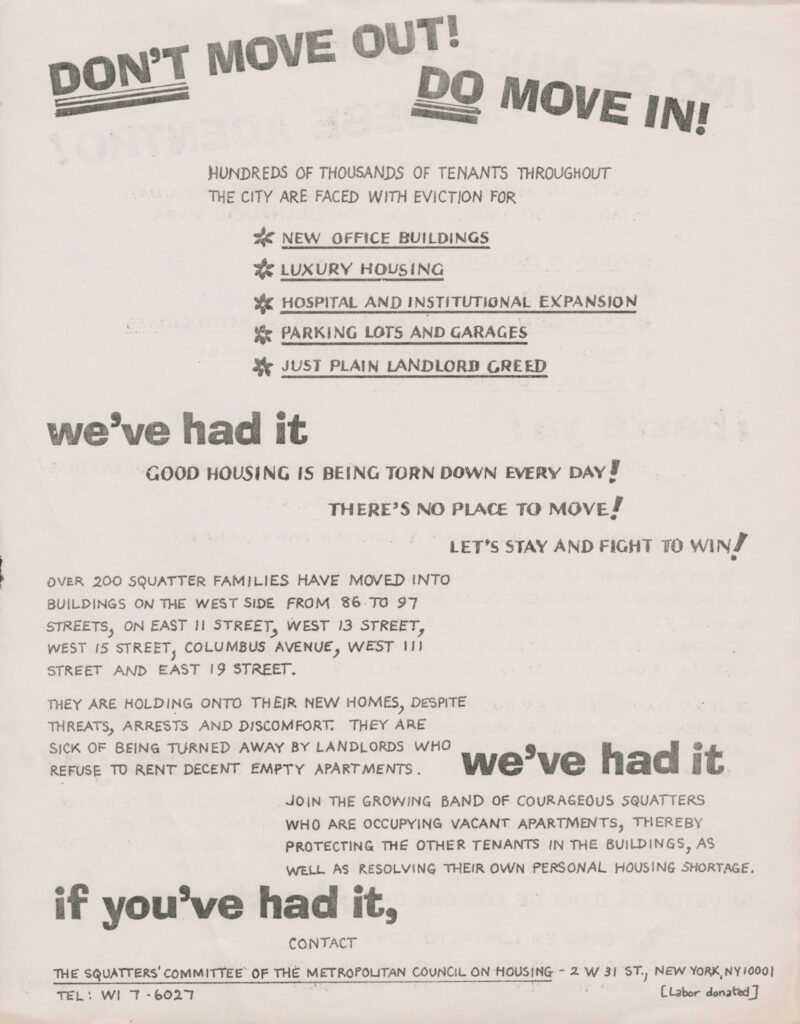

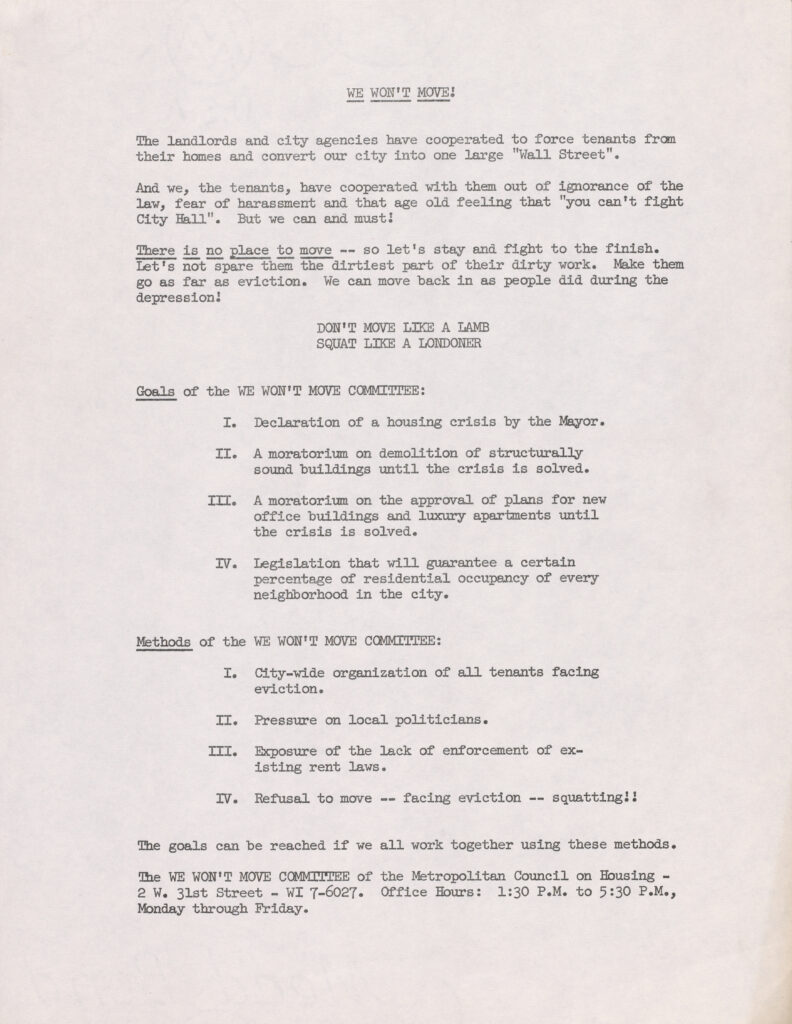

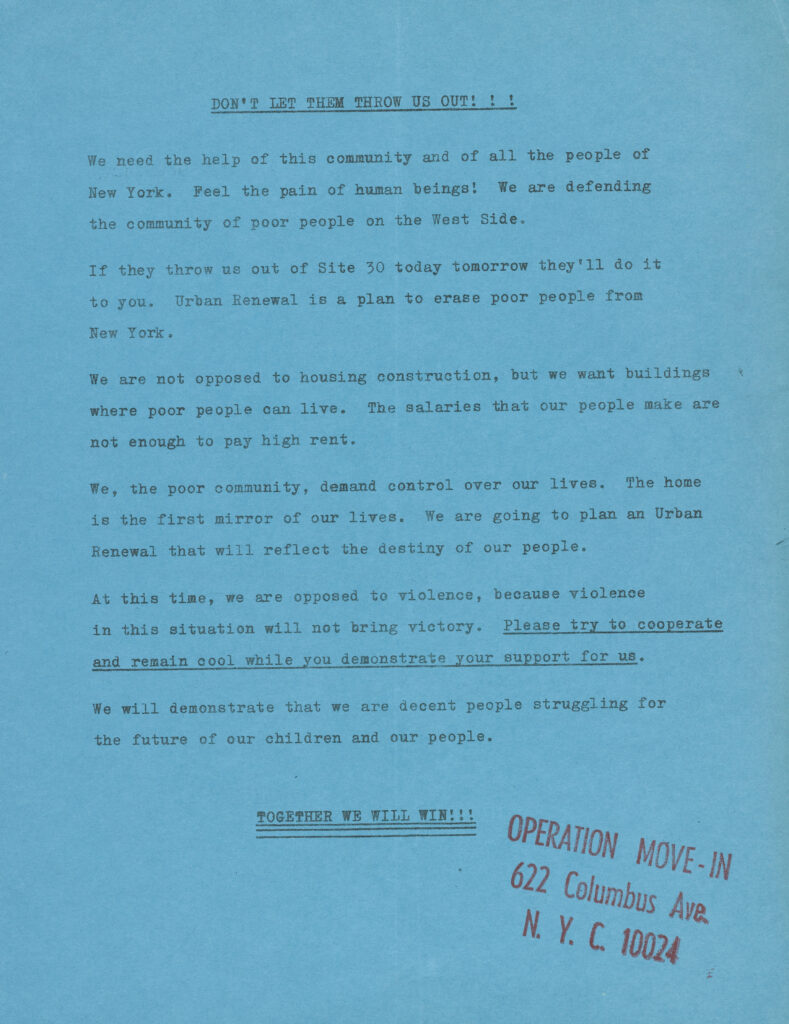

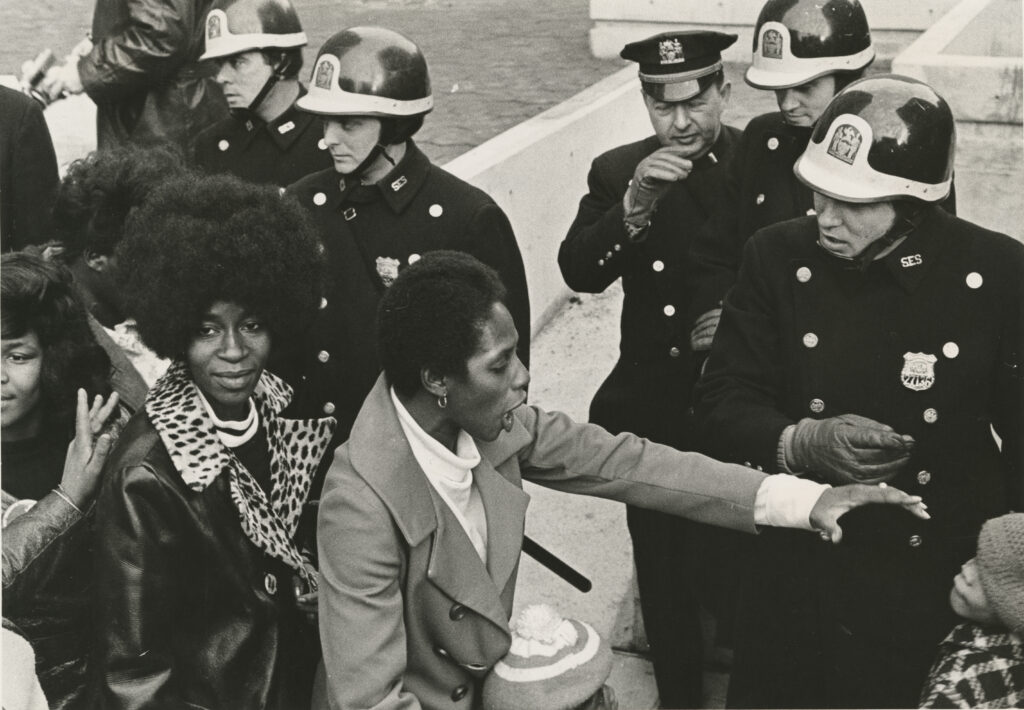

Operation Move-In

When landlords anticipate redevelopment or luxury renovations that will increase rental values, they often hold apartments intentionally vacant, a process known as “warehousing”. During the summer of 1970, a squatter movement installed over 300 families in warehoused apartments across the city. Most of these squatted apartments, frequently slated for demolition in urban renewal areas, were owned by the city or by large institutions. Led by African-American and Latino families, the squatter movement gained significant media coverage, giving exposure to critical housing issues such as urban renewal, property speculation, long-term vacancies, and the shortage of affordable housing.

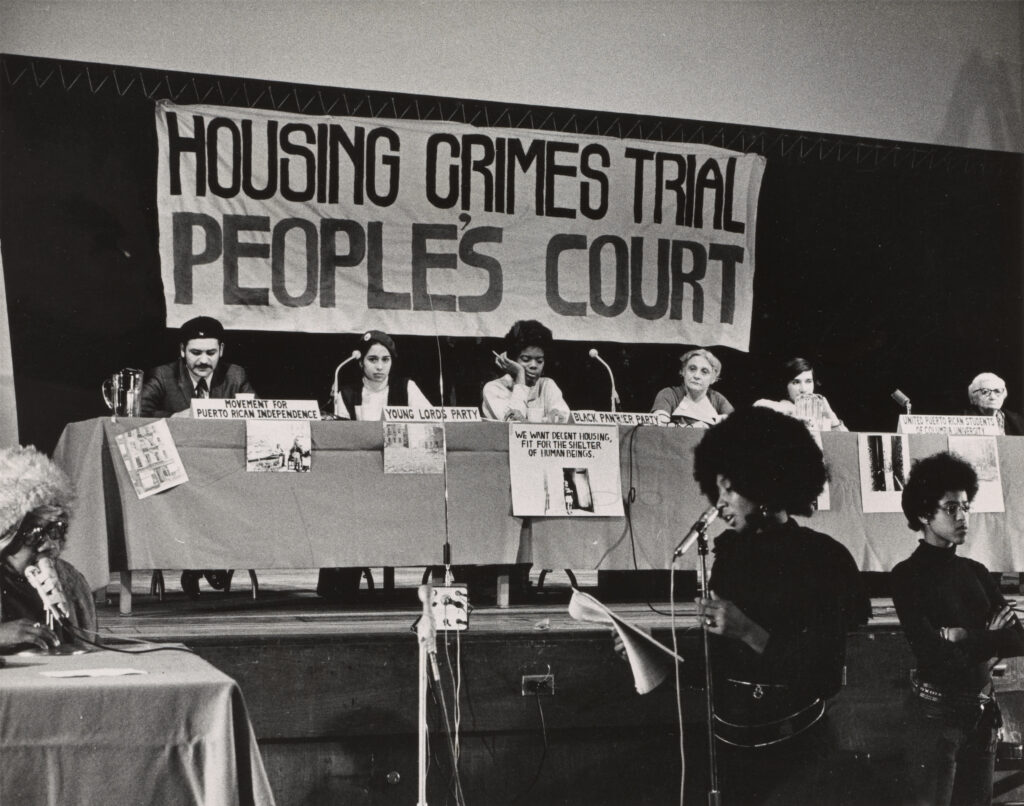

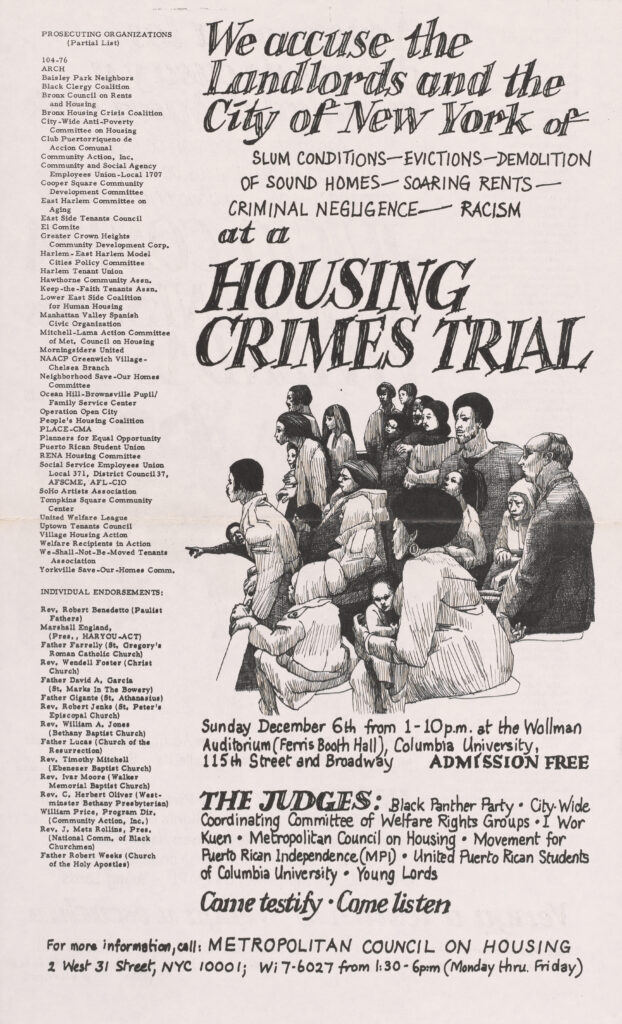

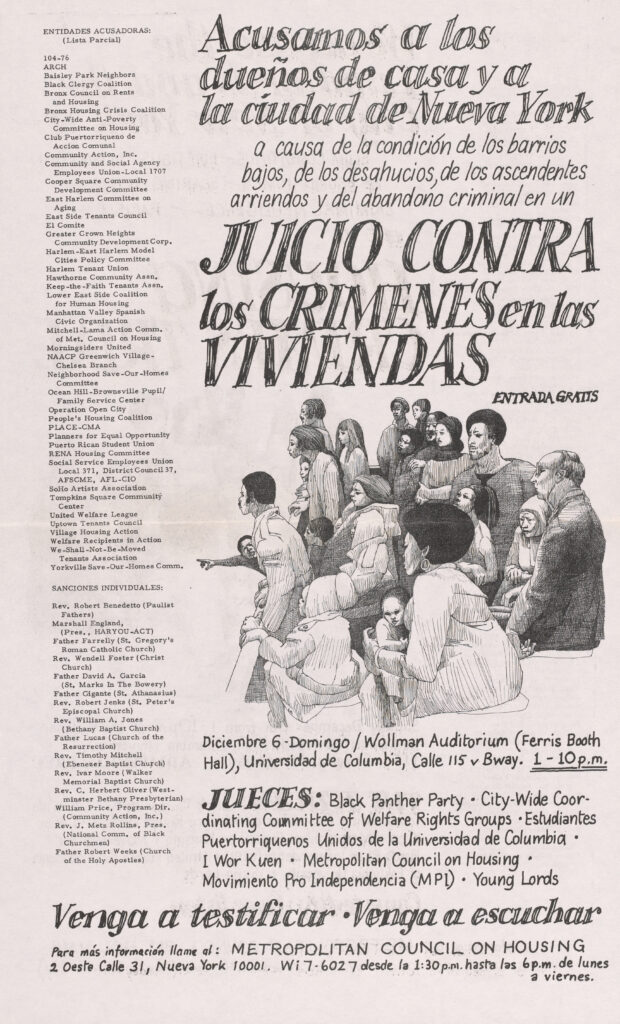

Housing Crimes Trial

In December 1970, the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, I Wor Kuen, the Movement for Puerto Rican Independence, and the Metropolitan Council on Housing organized a mock trial called the People’s Court Housing Crimes Trial. Tenants, squatters, and sympathetic city officials testified about the poor housing available to low-income residents. The event successfully brought together a multiracial, intergenerational group of people working on housing issues in New York City, as well as uniting liberal and radical organizers.

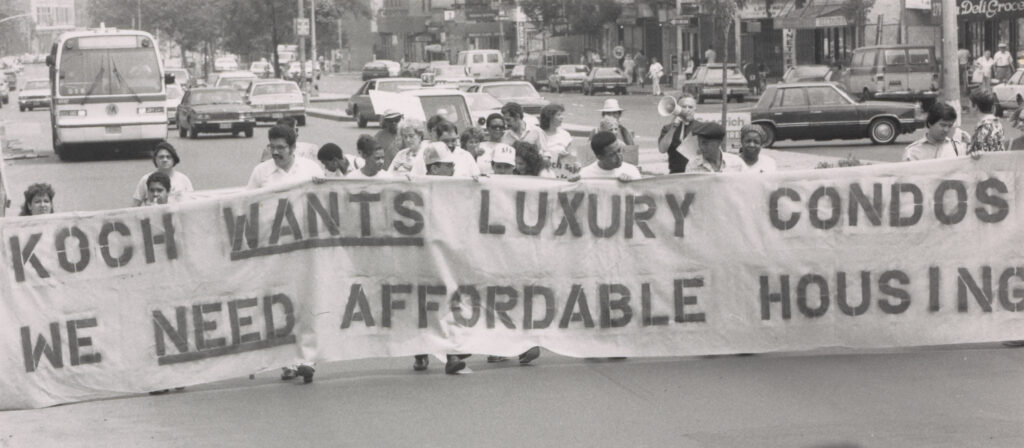

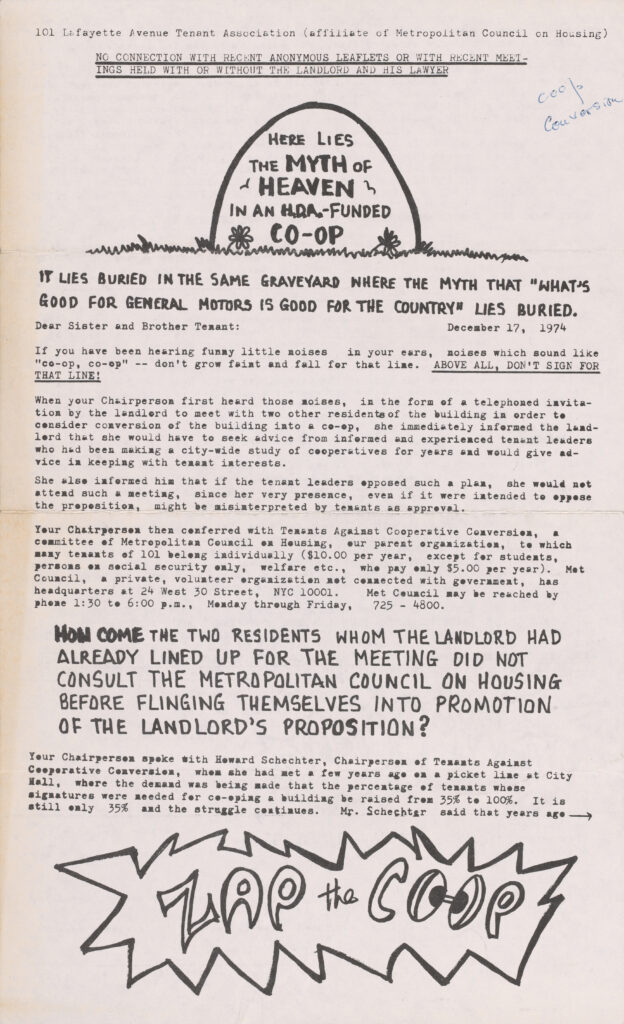

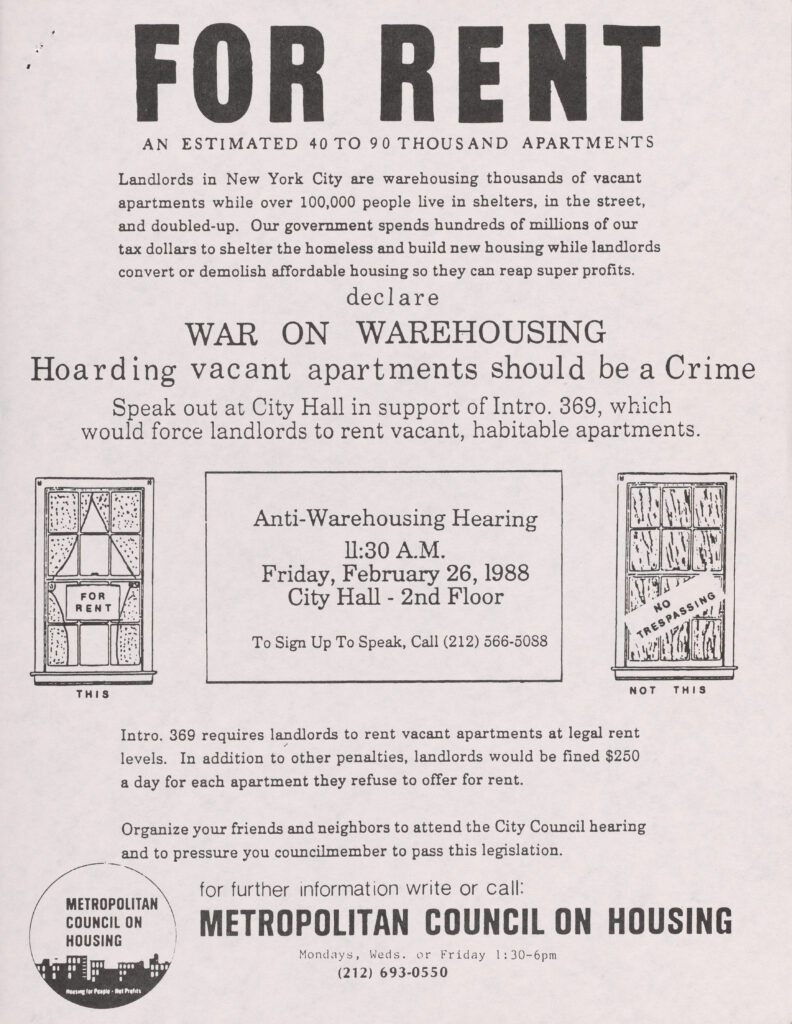

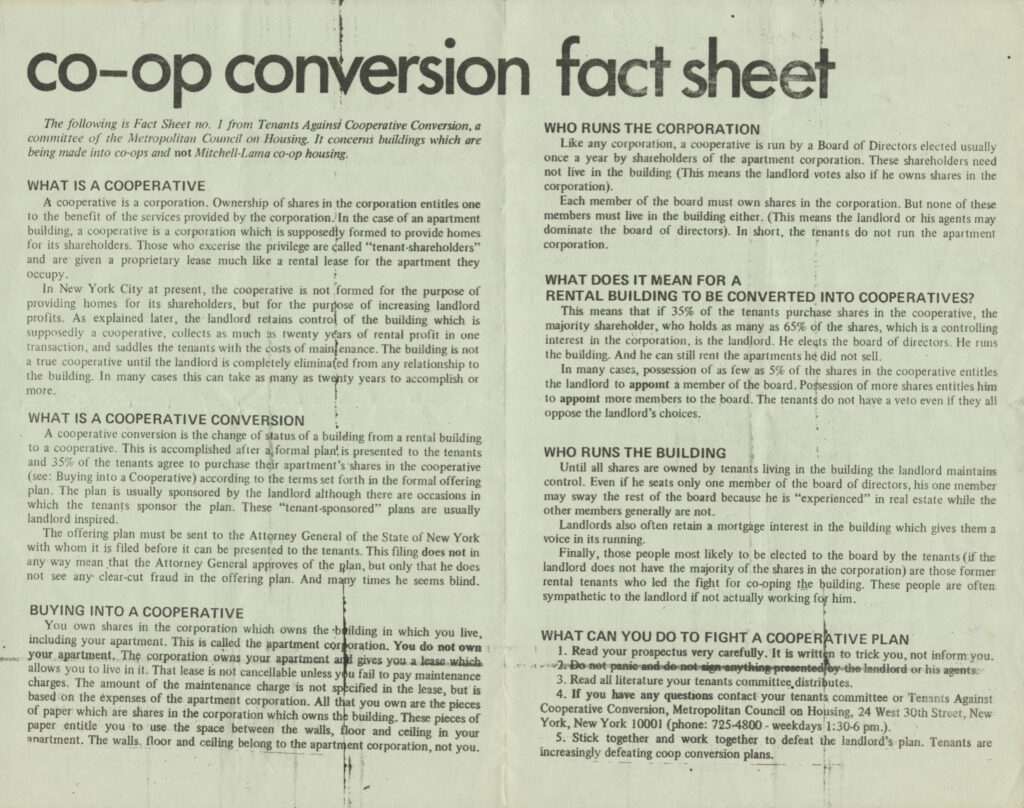

Co-op Conversion

As the city rebounded from the 1970s financial crisis, new threats to tenants emerged during the 1980s. Co-op conversion allowed landlords to convert their rental apartments into market-rate cooperatives or condominiums. The regulations for co-op conversion allowed vacant apartments to be sold at higher costs, increasing the incentive for landlords to warehouse vacant apartments in preparation for conversion. By the late 1980s, a New York State survey estimated that between 40,000 and 100,000 apartments were being warehoused annually.

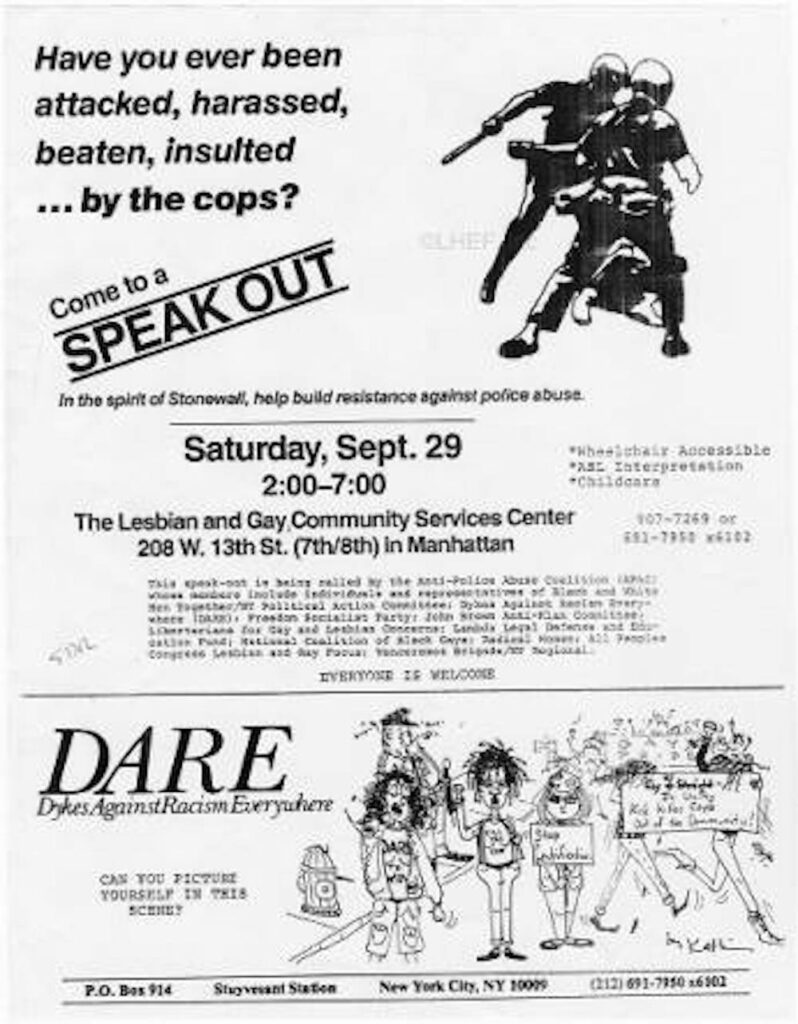

Queer Tenants Organize

Dykes Against Racism Everywhere

Dykes Against Racism Everywhere (DARE) was a multiracial direct action group based in the Lower East Side. A radical lesbian organization, DARE’s working groups constructed a complex political agenda centering anti-racism while creating connections to other struggles. A DARE flyer explained the relationship between policing and gentrification.

“We feel that the housing struggle is crucial in the fight against racist and economic oppression… For lesbians and gay males generally, and for Third World people in particular, the increased police harassment that accompanies gentrification makes it more and more difficult just to walk down the street without being assaulted by the cops.”

(DARE flyer)

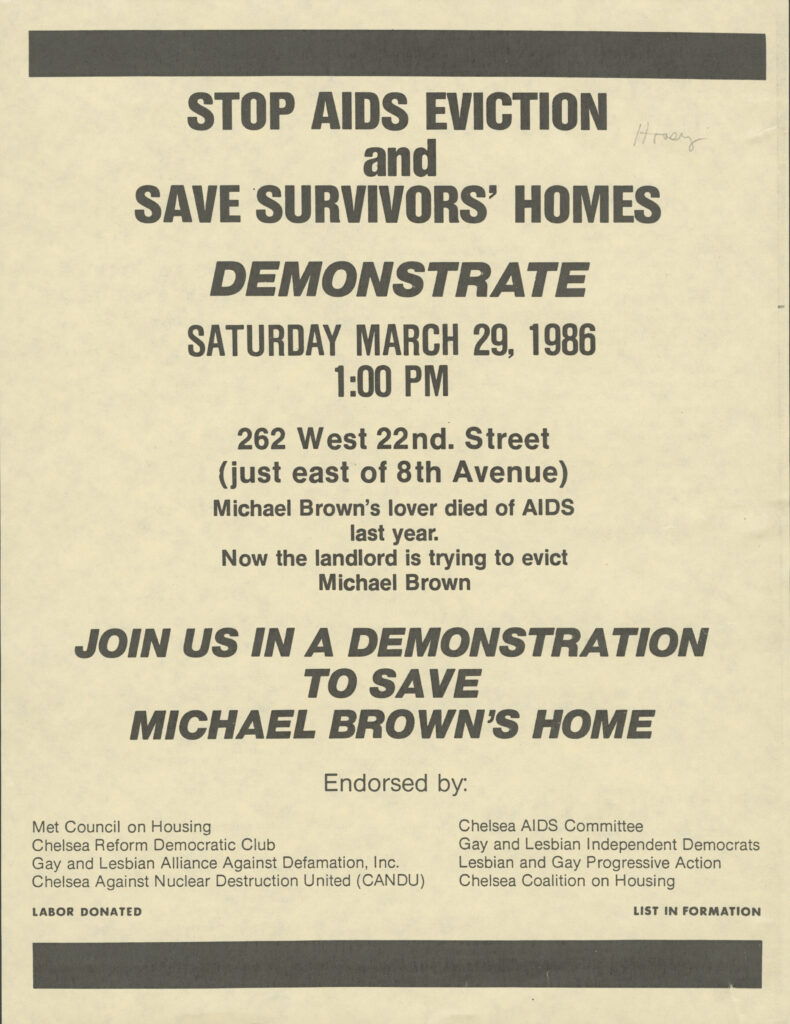

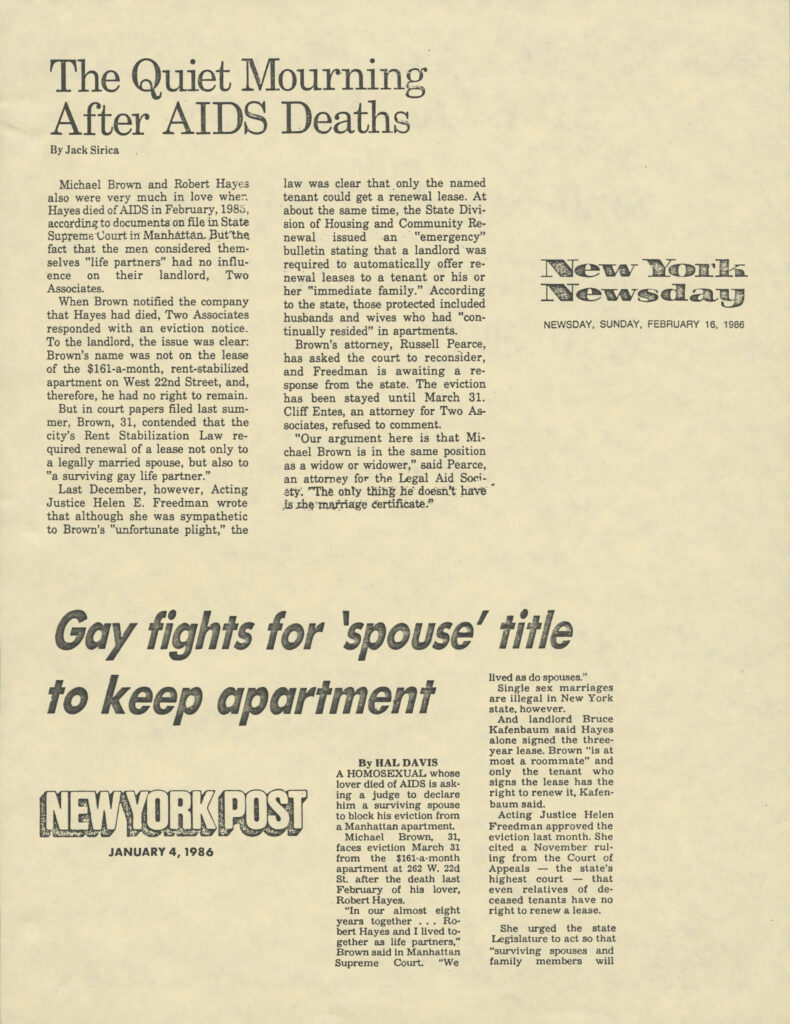

Ending AIDS Evictions

In 1981, the AIDS epidemic began in NYC, and over the course of the following decade almost 20,000 New Yorkers died. During the 1980s, people with AIDS had few legal protections, and the death of a leaseholder resulted in the eviction of the surviving tenant. The tenant movement rallied to save the homes of survivors. In 1989, following protests and press coverage, nontraditional family members gained the right to remain in their homes when the tenant of record dies.

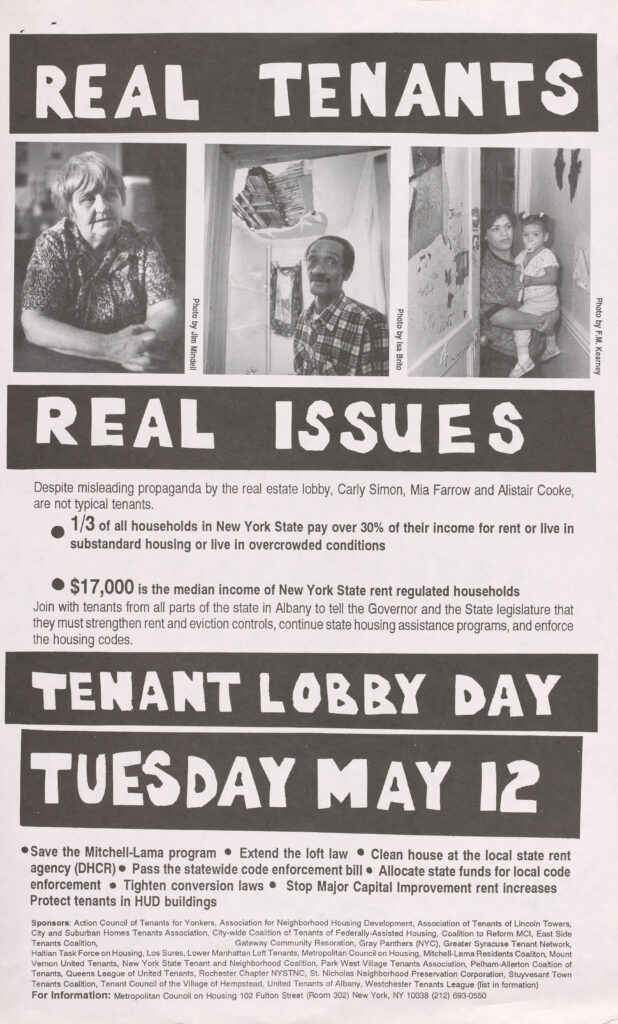

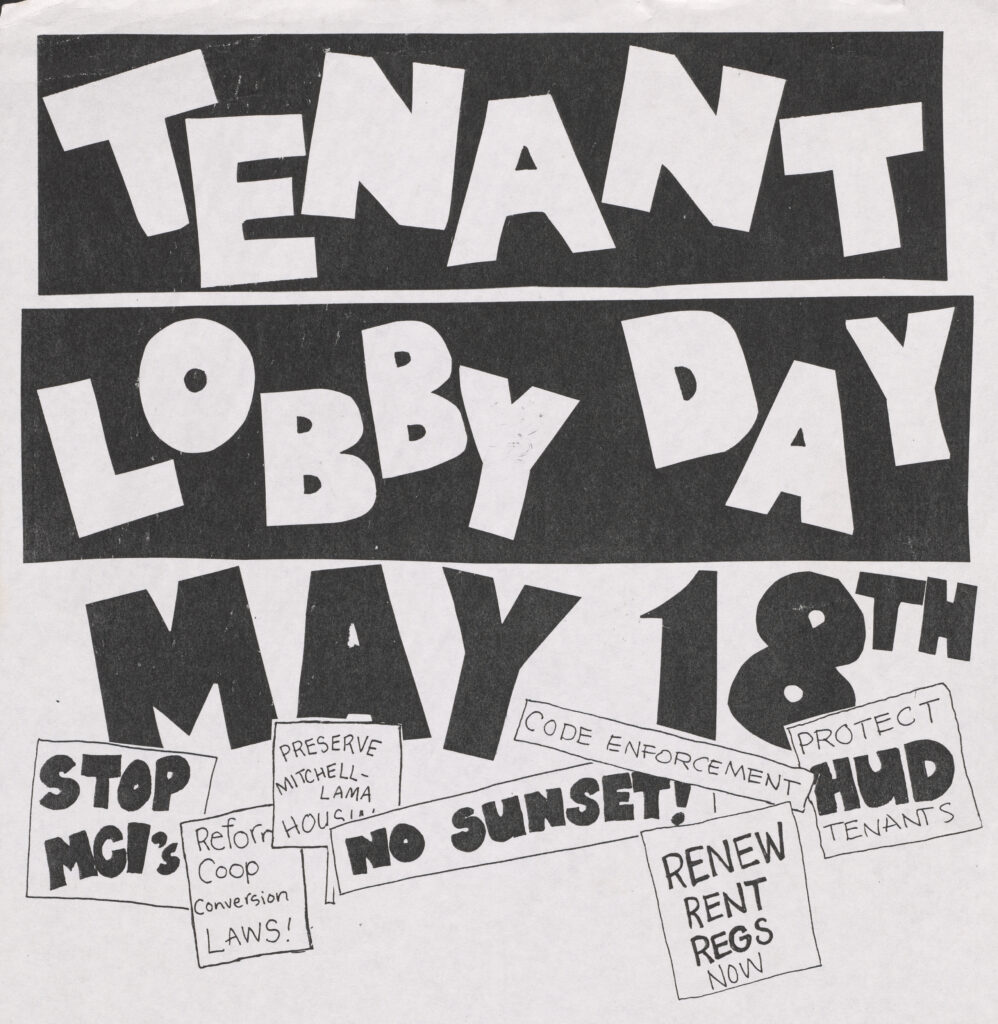

Renewing the Rent Laws

For many years, New York State’s rent regulation laws expired after a set period of time, and therefore required periodic renewal. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the real estate and landlord lobby successfully weakened the rent regulation laws during renewal periods. The 1993 renewal introduced Temporary High Rent Vacancy Deregulation (which deregulated apartments renting for over $2,000 per month) and Temporary High Income Rent Deregulation (which deregulated apartments for tenants with household incomes over $250,000). The 1997 renewal introduced 20% rent increases on all vacant apartments, and placed new limitations on the power of housing court. In 2003, preferential rents were introduced, allowing landlords to offer rents below the legal maximum in exchange for latitude to impose steep hikes upon renewal. Overall, these changes to the rent regulation system have resulted in the deregulation of tens of thousands of units of housing. In 2019, tenants successfully reversed the rollback and won many new protections: rent regulations are now permanent (eliminating periodic renewals), apartments are no longer deregulated when they meet a certain rent threshold, the 20% vacancy bonus was eliminated, preferential rents became permanent for current tenants, Major Capital Improvements (MCI) rent increases were made subject to tighter regulations, and the formula for calculating rent increases for rent controlled tenants was updated.

Current Campaigns (2015)

Developed in collaboration with tenant organizations from across the city, this section examines current campaigns against predatory equity, tenant harassment, the cluster-site shelter program, vacancy decontrol, and gentrification-driven policing. Building on a history of effective and militant organizing, tenants today continue to demand decent and affordable housing for al New Yorkers.

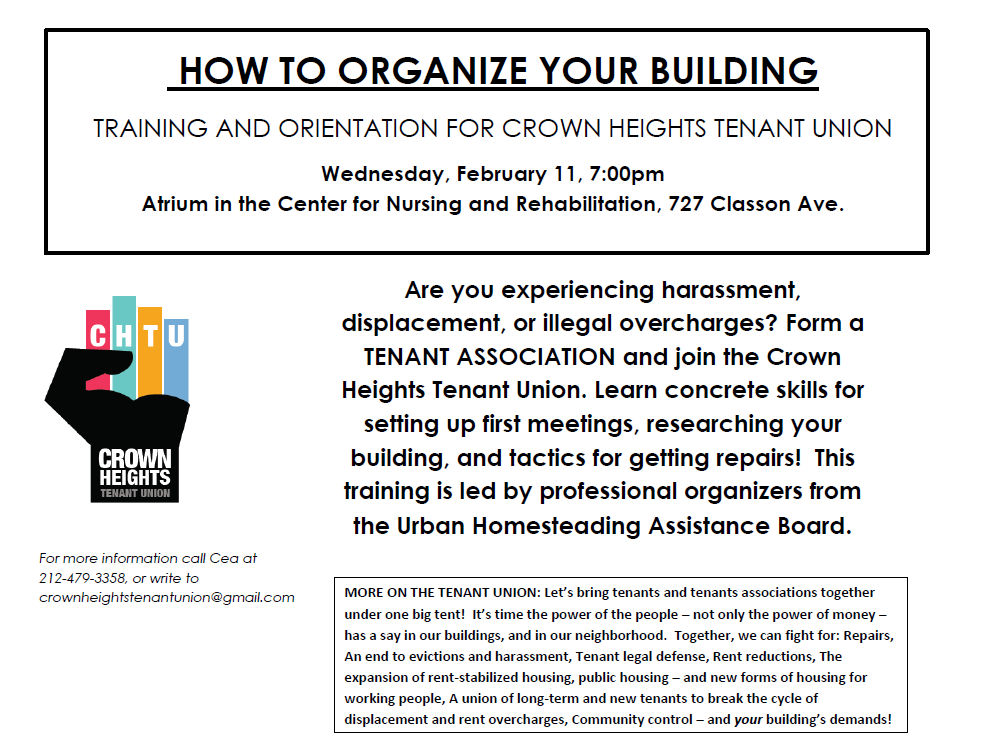

Crown Heights: Predatory Equity

Predatory equity refers to the financing of building purchases based on “projected” hiked rents, not current rents. New landlords use a variety of tactics, including harassment, decreased services, and aggressive buyouts, to force long-term residents to leave in favor of new, higher-income tenants. Long-term and new residents have united in the Crown Heights Tenant Union (CHTU) to fight for stricter enforcement of existing tenants’ rights in addition to new, stronger protections that eliminate loopholes in the law that favor landlords. On January 10, 2015, CTHU held an emergency rally that successfully got the heat and hot water restored at a Crown Heights apartment building owned by ZT Realty.

Lower Manhattan: Tenant Harassment

Rent-regulated tenants in Manhattan also face harassment by predatory landlords and developers. In Chinatown, CAAAV research revealed that three quarters of tenants have experienced harassment, including refusal of rent payments; taking tenants to court without a basis for eviction; and collecting names of all those living in the apartment. The Marolda Properties Tenant Coalition organized against the harassment, and in 2014, the state Tenant Protection Unit opened an investigation into Marolda Properties. Nearby, the Cooper Square Committee (well known for its work against urban renewal in the 1960s) is pressing the Department of Buildings to bar needlessly onerous renovations, another tool used to harass tenants.

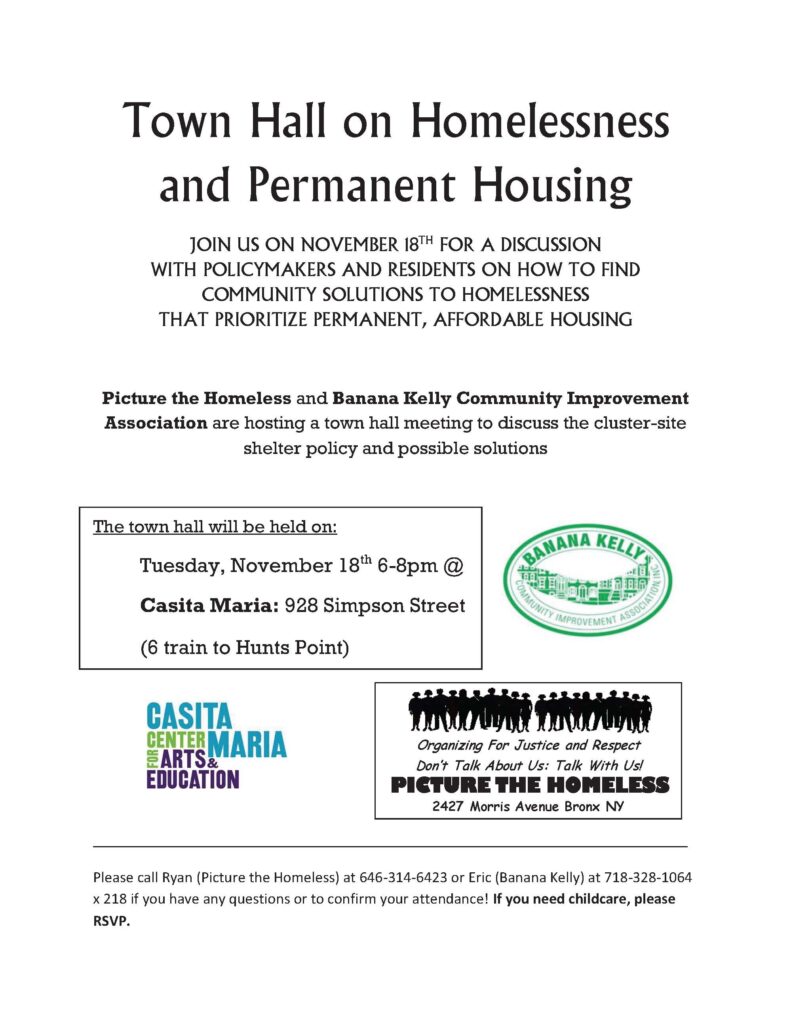

South Bronx: Cluster-Site Shelter Policy

Cluster-site shelters are private, rent-stabilized apartments where the NYC Department of Homeless Services pays up to $3,565-a-month to temporarily house homeless families. The policy rewards landlords for turning rent-stabilized apartments into temporary shelter, reducing the overall supply of long-term affordable housing in low-income neighborhoods. Banana Kelly CIA and Picture the Homeless have united in a campaign to end the cluster-site shelter program in favor of a subsidy that would directly support homeless people in finding permanent, affordable housing.

Housing Court Reform

During 2012, Bronx Housing Court ordered evictions of approximately 11,000 families. The vast majority of tenants in the Bronx (and across the city) do not have legal representation at housing court, which places them at a huge disadvantage. At least half of evictions would be prevented if tenants had an attorney. Community Action for Safe Apartments (CASA), Banana Kelly CIA, and others, have united in the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition to demand that tenants in housing court have a right to defense by licensed, qualified, and experienced attorneys.

Flatbush: Vacancy Decontrol

In Flatbush, as in other areas, rent-stabilized housing is under attack by predatory lenders, harassing landlords, and vacancy decontrol. Because 70% of Flatbush residents are rent-stabilized, the struggle is acute – the neighborhood lost 3,500 units of rent stabilized housing due to these causes between 2008 and 2011. The Flatbush Tenant Coalition is a group of fifty neighborhood tenant associations that organize in their buildings and provide leadership in citywide campaigns for stronger rent laws and housing court reform.

Policing

Equality for Flatbush organizes in the same neighborhood to expose the connections between the loss of affordable housing and aggressive policing. Police repression, like tenant harassment, makes neighborhoods unlivable for long-time residents, who are often people of color. Equality for Flatbush is conducting a six-month survey on police checkpoints in Flatbush and a solidarity campaign with dollar van drivers.

South Williamsburg: Luxury Housing & Gentrification

Currently the South Side of Williamsburg is facing extreme gentrification due to the area becoming increasingly attractive to wealthy individuals and investors over the past decade. With high profits in mind, landlords have used different tactics to displace their low-income tenants, including construction harassment, buy-outs, and neglect to repairs. Southside United HDFC – Los Sures® works aggressively to directly assist, educate, and organize tenants to prevent their displacement. The group also collaborates with other community groups and coalitions as a united front against tenant displacement.

Current Campaigns (2022)

Following the tenant victories of 2019, the NYC and state-wide tenant movement has organized to pass Good Cause eviction, which would protect every tenant (including those in unregulated or “market rate” housing) in New York State from unjust eviction and unreasonable rent increases. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, tenants have organized to implement and extend unprecedented eviction moratoriums at the state and federal levels, which protected most New Yorkers from eviction until the moratorium lapsed in January 2022. Building on a history of effective and militant organizing, tenants today continue to demand decent and affordable housing for all New Yorkers.

Right to Counsel

In 2017, after a hard fought grassroots campaign, New York City became the first in the nation to establish a Right to Counsel for tenants facing eviction. The campaign inspired a national movement – now three states and seventeen cities have Right to Counsel. Currently the Coalition is working to ensure that the new law is implemented in a way that upholds housing as a human right, builds tenant power, transforms the nature of the courts, and furthers the dignity and humanity of every tenant. A campaign to extend the Right to Counsel to all tenants in New York State is ongoing.

Ending Cluster-Site Shelters

Cluster-site shelters are private, rent-stabilized apartments where the NYC Department of Homeless Services pays up to $3,565-a-month to temporarily house homeless families. The policy rewards landlords for turning rent-stabilized apartments into temporary shelter, reducing the overall supply of long-term affordable housing in low-income neighborhoods. Banana Kelly CIA and Picture the Homeless united in a years-long campaign to successfully end the cluster-site shelter program in favor of a subsidy that would directly support homeless people in finding permanent, affordable housing. This campaign pushed the city to shut down the program and purchase a number of buildings from one of the worst cluster-site operators. Banana Kelly took ownership of four of those buildings, and now offers services to residents, is renovating the buildings, and incorporating them into Banana Kelly’s organizing work and Resident Council. As of 2021, the city had closed 95% of the cluster-site units that existed at the program’s peak in 2016.

Extending the Victories of 2019

Since the 2019 tenant legislative victories, the Cooper Square Committee has been fighting the loopholes left in the law, including apartment combination (known as Frankensteining) and the warehousing of affordable apartments. Cooper Square Committee also supports tenants as they fight for repairs, lease renewals, and face harassment, particularly the notorious practice of construction as harassment, during which tenants can experience excessive noise, debris, and dust (which often contains lead). One of Cooper Square’s biggest and most active tenant coalitions, Tenants Taking Control, was a major part of two Attorney General settlements and saw their previous landlord become the first person to be permanently banned from New York real estate.

In Flatbush, as in other areas, rent-stabilized housing remains under attack by predatory lenders and harassing landlords. Because the majority of Flatbush residents are rent-stabilized, the struggle is acute. The Flatbush Tenant Coalition has focused on strengthening Right to Counsel, including supporting the successful campaign to accelerate the implementation of the program across the city.

As members of the state-wide organization Housing Justice for All, the Cooper Square Committee and Flatbush Tenant Coalition have organized to extend the eviction moratorium, educate their communities, and support tenants in applying for rental assistance. Following the end of the eviction moratorium in New York State, organizations across the city have demanded that Housing Court slow down eviction proceedings to ensure that all tenants have adequate legal representation.

Rezoning

Communities across New York City, from Inwood to Astoria, have fought rezonings that would bring large-scale development and luxury housing. CAAAV, in partnership with Tenants United Fighting for the Lower East Side (TUFF-LES) and Good Old Lower East Side (GOLES), is organizing to pass the Two Bridges Community Plan for the waterfront neighborhood between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges. The Two Bridges neighborhood is fighting a mega-development that would bring five super-tall towers of luxury housing. The community plan, part of a larger community development plan for Chinatown, promotes mixed-use development and the creation of new affordable housing to serve the historically diverse, low- and moderate-income neighborhood.

Policing and Gentrification

Equality for Flatbush (E4F) organizes to expose the connections between the loss of affordable housing and aggressive policing. Police repression, like tenant harassment, makes neighborhoods unlivable for long-time residents, who are often people of color. Since 2013, E4F has fought the racial profiling and economic harassment targeting dollar van and cab drivers along Flatbush Avenue, Church Avenue and Utica Avenue. In spring 2020, E4F supported the largely POC and LGBTQ+ residents of 1214 Dean Street, who were experiencing landlord harassment and attempted eviction during the first months of the pandemic, coordinating hundreds of people to participate in a multi-day eviction defense. In 2022, the tenants won a civil suit against their landlords.

Exhibition Dates

March 26, 2015

June 15, 2015